Inside Sharpstown's Sugar Grove Academy: How HISD's New Education System Works in a Middle School

The timer on the SMART Board screen clocks down to zero as nineteen sixth graders jot examples of figurative language in their notebooks. They’re searching for them in a poem on screen that begins, “The sun smiled like a friend.”

The timer chimes.

“Marco,” says Ms. Evans.

“Polo,” reply the students.

Crystal Evans is using one of many Multiple Response Strategies (MRSs): ways to get feedback from every student in the class at the same time. Some MRSs help teachers gauge the students’ learning. Others, like this one, just serve to regain students’ attention after they’ve been working on activities or discussing.

“If you don’t know what we’re doing today, where can you find that?” asks Evans.

The students point to a whiteboard section left of the SMART Board. Inside a taped two-by-two grid, the day’s Lesson Objectives, Demonstration of Learning description, Essential Vocabulary, and Essential Question have been written in marker.

Evans switches to the next SMART Board slide and points to an example of a metaphor. “Now, is her laughter really music?” she asks.

This is the beginning of a sixth-grade English Language Arts class at Sugar Grove Academy, one of four schools in Sharpstown that underwent massive changes this school year through HISD Superintendent Mike Miles’s controversial New Education System (NES).

Miles promised to improve reading curriculum, boost test scores, and prepare students for the “Year 2035” workforce. But critics have claimed that Miles is hurting students by “turning libraries into discipline centers” (a stock phrase in the media by this point)—and unnecessarily restricting teachers by imposing standardized lesson plans and the use of timers.

Amid all the noise, what is it really like inside an NES school?

At Sugar Grove, Miles-appointed Principal Noe Ortega has replaced Ericka Austin. On the morning of November 30, 2023, Ortega—sporting a navy blue suitcoat and a short, black faux hawk—stands near a small table in a hallway divided by orange cones. He greets students in Spanish as they walk up and down the stairs.

Ortega and his assistant principals stay in the hallways during transitions to make sure everything goes smoothly. The rules require the school’s 802 students to walk on the right side of the cones. And the new dress code means that teachers can tell a student’s grade level at a glance: sixth grade wears red, seventh wears grey, eighth wears blue.

After the students disappear into classrooms, Ortega takes me up the stairs into Ms. Evans’ class.

Phase 1: Direct Instruction

In the NES, math and ELA classes run for 90 minutes, starting with 45-55 minutes of direct instruction. But that doesn’t mean 50 minutes of traditional lecturing. Instead, teachers are required to use MRSs at least every seven minutes, although some do it more often.

Evans and her sixth graders start analyzing Barack Obama’s 2008 victory speech.

Down the hall, Islam Helmy’s sixth grade ELA class is analyzing the same speech, but Helmy is focusing on a different portion. Evans used the “turn and read” strategy—asking students to read part of the speech to their partners—while Helmy is reading a section out loud to his twenty-two students. Helmy’s slides look different too.

Even though the district provides standardized lesson plans, Ortega says he encourages teachers to modify the slides and “add their own personality.”

The kids listen to Helmy quietly, trading smiles, until he asks them to discuss at their tables.

Across the hall, Kierra Richardson teaches sixth graders how to use a number line to add positive and negative numbers. Jerson Medina, a multilingual tutor, hovers over some of the nineteen students, pointing to pages and speaking softly.

Ortega says Medina is here because this class has several “emergent bilingual Spanish speakers.”

Richardson asks her students to do the “turn and talk” MRS, meaning they have one minute to discuss at their tables before she calls on two groups to “share out.”

Down the hall, Dyonna Scott—the school’s October Teacher of the Month—is teaching the number line with the assistance of a teacher apprentice and a SPED coach.

Scott asks her students to do the whiteboard MRS: the students write down their answers to a question on their personal whiteboards, then all hold up their whiteboards at the same time. This question is “What is -3 + 5?” Nearly everyone guesses the correct answer, two.

Phase 2: Demonstration of Learning

After direct instruction, each student receives a Demonstration of Learning (DOL) worksheet. To prevent cheating (students sit two or three to a table), one student at each table sets up a blue trifold board surrounding his or her personal space. They have ten minutes to finish (with extra time for students who need it, says Ortega).

Each worksheet has five questions and gets scored in class. Based on their DOL score, each student gets a new worksheet from a set of colored bins on the side of the room: green for students who scored 5/5, blue for 4/5, yellow for 3/5, and red for 0-2/5.

The students who pull from the red and yellow bins get the least advanced worksheets. Since they haven’t displayed understanding of the lesson, they’re staying in class for the re-teach.

What about the students who get at least four out of five questions right? They get sent to the Team Center.

Phase 3 (Version 1): Team Centers

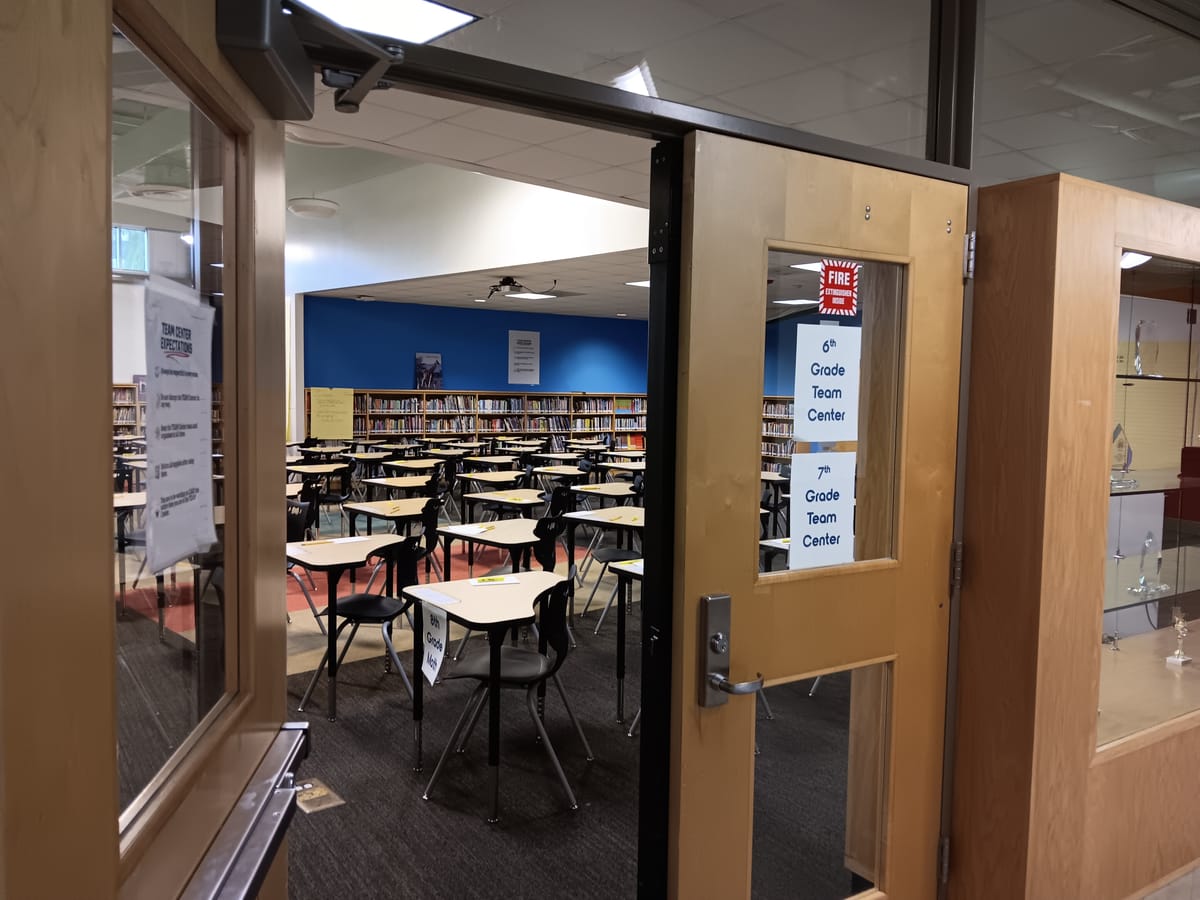

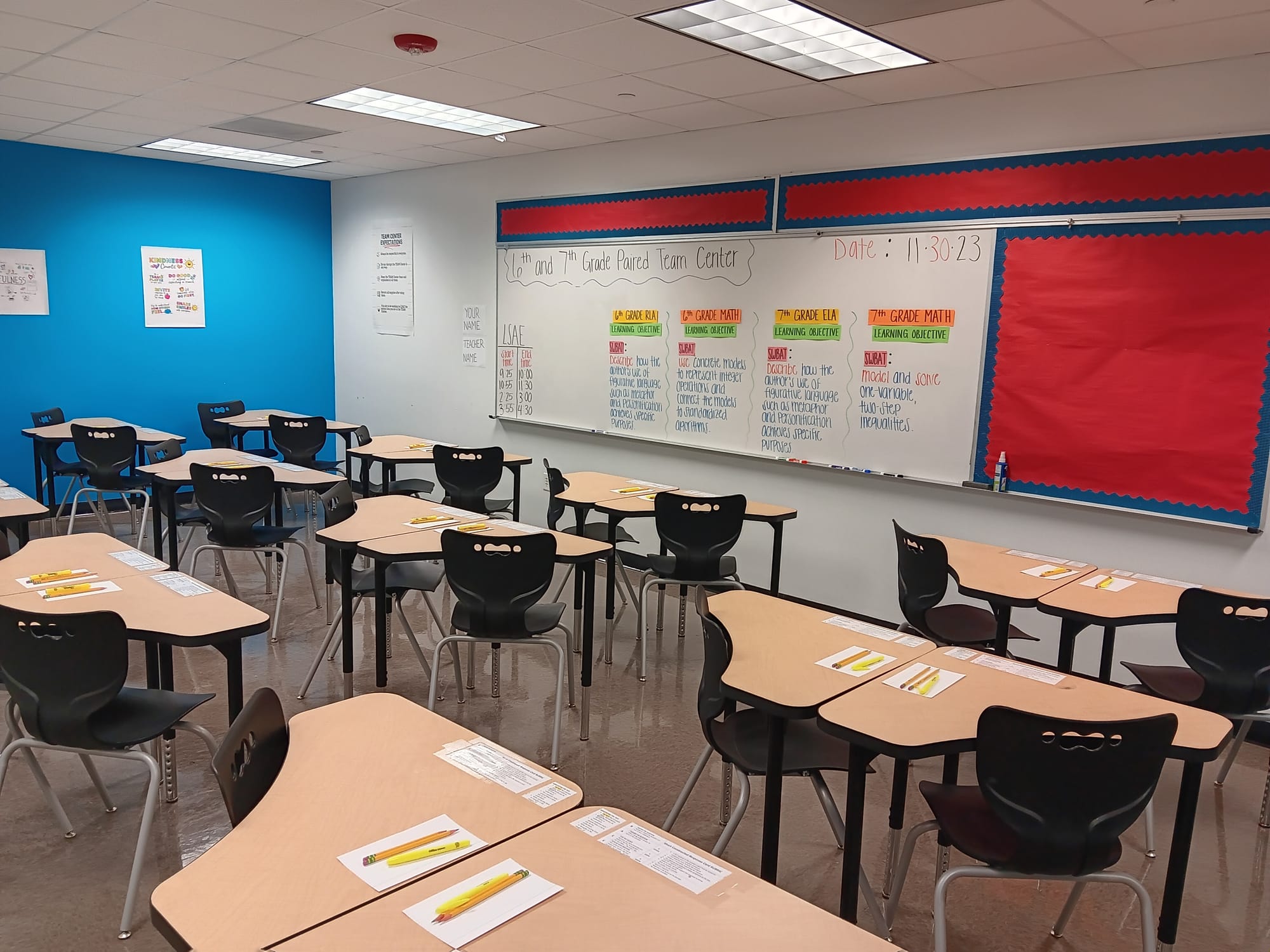

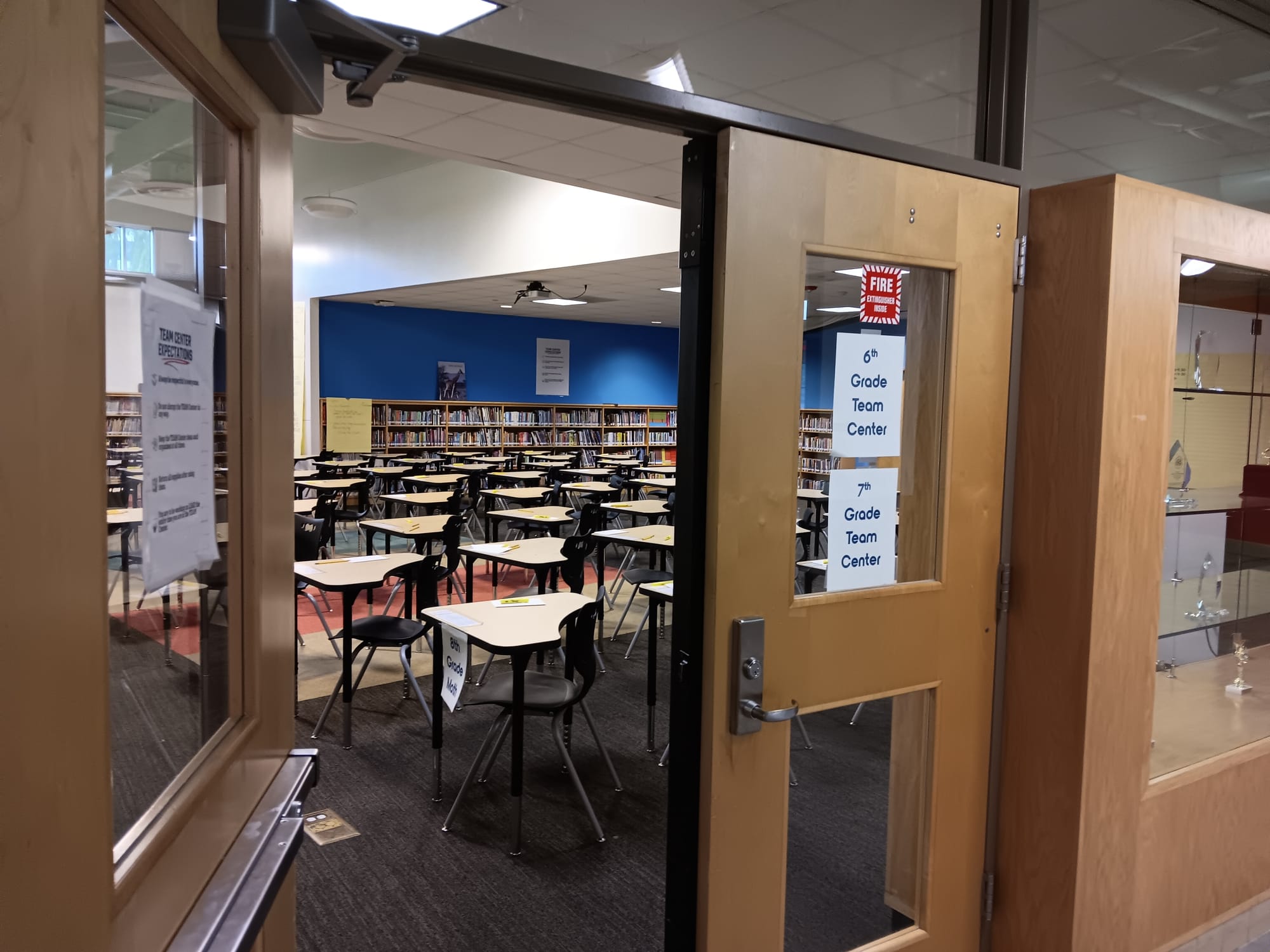

Although it’s often called a “discipline center” by other media outlets, the Team Center is primarily a place for advanced students to do advanced work, at their own pace, in return for rewards.

Team Centers aren’t just former libraries, either. There are four Team Centers at Sugar Grove, and three are former classrooms.

In the sixth and seventh grade Team Center, which used to be Sugar Grove’s library, at least sixty students complete the worksheets they got from the green and blue bins. Learning coaches move around the room, grading students’ worksheets and putting them in folders to give to their teachers.

If the students do well, they can earn tickets that say, “Congratulations! You leveled up your game at the Team Center,” which they can turn in for prizes.

In a smaller room within the library, seven students wearing headphones are Zooming in to class because they were pulled out due to discipline issues.

Sugar Grove doesn’t have a librarian anymore, but hundreds of books line shelves along the walls—and they aren’t behind lock and key. Ortega says that students are allowed to read the books and take them home.

Phase 3 (Version 2): The Re-Teach

While the students who grasped the lesson the first time are studying in the Team Centers, the rest are still in class with their teachers.

In Jamie Davis’s classroom, the SMART Board reads “This coffee shop is an icebox.”

“What are we saying about the coffee shop?” Davis asks.

“It’s cold,” replies a student.

Davis, in a black-and-red “I Love Paris” shirt, is reteaching metaphors and similes to her eighth grade ELA students. She switches to the next slide, a reading passage about “the voice of the heart.” She has personalized the slide with images like a singing heart.

She points out a line in the passage—which compares fear to love—and asks whether it’s a metaphor, simile, personification, or hyperbole. It’s another whiteboard response: she gives the students about a minute to write down their answers.

The scattered answers of the students show that many still don’t get it. So she tells them it’s a simile and asks them to explain why.

Dyad Classes

In a downstairs classroom, a man named Matthew describes how his students have been fighting a caterpillar infestation in their basil plants. Today, he plans to have the students clean the hydroponics system with soap and water to eliminate all traces of the pests.

Matthew is a dyad instructor—a community member brought in to teach real-world skills through hands-on classes.

During first period, two other dyad classes are being taught in the cafeteria: theater in one corner, art in the other. The art students have been drawing eyes that contain “visions of their future or heritage,” says their teacher—anything from soccer to their home countries’ flags.

Co-Teaching

During the second period, Julie Nguyen and Hope Houston, new HISD teachers who transferred from Fort Bend ISD this year, are co-teaching Art of Thinking to ten eighth graders.

During direct instruction, they take turns teaching from the front and supporting from the side.

Houston says she loves co-teaching. At first, she thought, “This is my baby—nobody can help,” but she has since realized that “two heads are better than one.” It also helps that “one can be disciplining, and one can be teaching.”

What Is “Art of Thinking,” Anyway?

The “Art of Thinking” is not a usual school subject, but it’s being taught in every NES school.

Nguyen asks students to create a “T-chart”—a list of pros and cons—in their notebooks. The slide asks them to list and weigh “potential costs and benefits of joining the school’s basketball team.” Then Nguyen asks them to reveal their ultimate decisions on their whiteboards.

One student holds up “NO!”

Nguyen asks, “Did we base this decision on our chart, or did we make it based on our feelings?”

If there’s a theme for the Art of Thinking, that seems to be it: make decisions using logic rather than emotions. Houston, a former science teacher, tells me that “thinking is a science” that applies across all subjects. She says that instead of “making hasty decisions out of how they just feel,” students need to learn to “pause and think about it more.”

After playing a two-minute video about opportunity cost, Nguyen gives students the personal example of her own decision to move from FBISD to Sugar Grove and why she thinks the cost was worth it. Then she asks students to give their own “real-world examples” of opportunity cost.

Classroom Observations

When Principal Ortega walks into a room, teachers and students don’t show much of a reaction. Ortega says that’s because they’re used to being observed regularly by himself and the assistant principals. (The NES involves frequent feedback for teachers.)

He also stops by several tables and asks the students about what they’re learning.

Curriculum Still Has Errors

HISD has been hiring “teacher experts” to vet curriculum after concerns were raised about errors and inappropriate content.

There’s still room for improvement.

At Sugar Grove, some lesson slides have grammar mistakes: “Write down as many figurative language as you can find in this poem” and “What do you think opportunity cost mean?”

In Ms. Evans’ class, a multiple-choice question on a slide asks students to interpret a line (from President Obama’s 2008 victory speech) about people who “put their hands on the arc of history and bend it once more toward the hope of a better day.”

Students write their answers on their whiteboards. At least eight students guess C, which says that Obama used his metaphor to “Convey the notion of individuals collectively shaping a brighter future.”

However, according to Ms. Evans and the answer key, the correct answer is A: Obama used his metaphor to “Depict the physical transformation of historical records.”

But C is certainly a better answer than A.* Obama wasn’t talking about tampering with historical documents (at least, hopefully not). He was talking about turning the trajectory of history toward a better future.

Thoughts from a Teacher

Unsurprisingly, Ms. Evans says that the school has had “a couple challenges” trying to make the curriculum align with the TEKS (Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills) standards.

But she also sees a bright side: “I was a little worried about [the NES] at first, but the structure is helpful.”

Structure seems to characterize the NES. The classrooms and hallways are orderly and quiet that morning.

The NES also pushes students to actively participate in their education. Principal Ortega describes the NES philosophy this way: “The kids take ownership of the learning—they’re doing the heavy lifting. It’s not just the teacher talking the whole time.”

This is just part of the story. I also want to hear about the NES from parents, students, and more teachers. Please email me at sharpstownsharpener@gmail.com or text me at 346-626-8355. And stay tuned for stories about other schools.

Correction: the multilingual tutor's name has been updated to Jerson Medina. Apologies for the previous misidentification.

*I might sound too opinionated here, but I am an English professor. And I’m pretty sure that you can see the right answer for yourself, too.

Comments ()