Being Homeless in Sharpstown: Leroy Conner’s Story

Under the bridge, Leroy Conner keeps things well-swept and trash-free. It’s where he lives, after all.

As semis rumble overhead on 59 and a fire engine wails by on the frontage road, Conner sits on a low metal railing, drinking a watermelon Arizona tea. In his jeans, checkered blue button-down shirt, black jacket, and blue baseball cap, he looks too well-dressed to be sleeping on the streets.

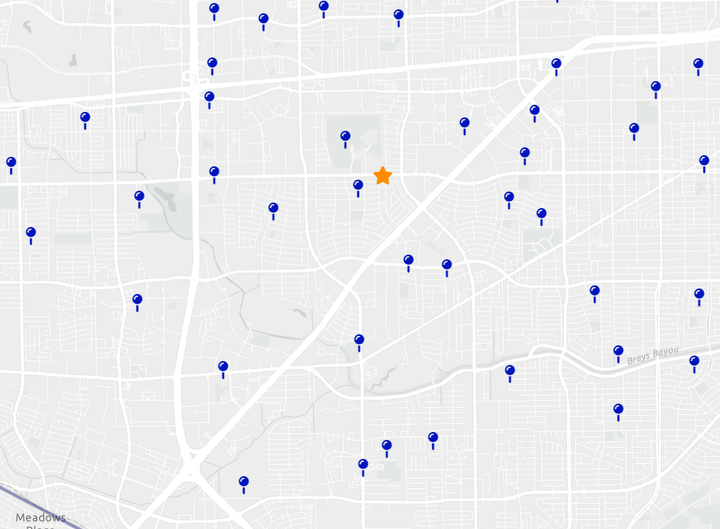

But he says he’s been homeless since he moved to Houston in 2006. During that time, he says, he only begged for money once. For income, he has worked a variety of temp jobs and handyman gigs. Lately, he’s been hitting construction dumpsters, salvaging copper wire, aluminum, and brass to sell for recycling: “I could probably tell you where almost every dumpster is in this city.”

He grew up in California but left in 2001 because he was “tired of getting locked up.” California had recently instituted a “Three Strikes and You’re Out Law," which meant that even petty theft could land someone in prison for 25 years if they had enough of a criminal record.

In 2006, Conner left Denver to work on flooded houses in New Orleans, where Katrina had left waterline marks above the garage ports.

In the second week, he got an itchy rash on his arm and realized it was probably due to the mold in the houses.

He decided to head “to who knows where.” When the bus stopped in Houston, he got off and stayed in a shelter downtown. In less than a week, the bumps on his arm disappeared.

He started “moving around,” staying at shelters like the Salvation Army and Star of Hope. But he didn’t focus on getting a full-time job.

In 2012, he “decided I was tired of being around shelter life.” He claimed that previously homeless people who became shelter staff “talked to me disrespectfully.” So he left.

For years, he bounced on and off the streets, staying everywhere from downtown tents to motels to efficiency housing units with shared showers, bathrooms, and kitchens. He especially disliked the efficiency units: “The people who frequent those kinds of environments are not good people.”

He says he never got an apartment because he didn’t have a full-time job. He worked, but it was “sporadic…not the type of money I could use to set aside for rent or bills.”

Eventually, he came to Sharpstown. He says he’s been under the same bridge along 59 for two-and-a-half years.

That’s where he met Dale Malone, who originally got his attention by making a mess under the bridge where they both lived. Conner says he convinced Malone to start cleaning the place more, and “Now we’re like the best of friends.”

Conner and Malone are both trying to get IDs as a step toward making it into housing. At age 64, Conner is fed up with life on the streets—it feels like he’s “barely alive.” So far, his efforts to get a Texas ID through DPS have been fruitless.

He says that the biggest challenge of street life is avoiding troublemakers, which is why he chooses his company “very carefully.” He says that’s how he's managed to stay in one place for so long.

But he worries that if he spends another year under the bridge, he might lose his sanity. “It’s killing me. I feel like here, I'm disabled."

Right now, he says “the only thing that keeps me sane is the fact that I have a Bible and I can read what true love is.”

If he gets off the streets, he says he would “start living again. Go to church on Sunday, cook meals, maybe get a part-time job.” He also has a daughter and granddaughter in California.

He’d like to get back in touch.

This is an as-told-by story. I have known Conner for months and Malone for years, but I have not rigorously fact-checked all of Conner’s claims about his life.

Conflict of Interest Statement: As described in another article, my friends and I have spoken with Conner and Malone several times as part of an unofficial homeless ministry, and I am currently trying to help them get IDs.

Comments ()