Climbing off the Streets, Part 2: Catch-22?

Last time, I said that it was “difficult” for a homeless person to get housing or a job without a photo ID. That was an understatement.

It’s more like a Catch-22.

Or, as Barbara Allen—executive director of Houston nonprofit Main Street Ministries—says a homeless man told her, “Not having an ID is like being the walking dead."

Here's why.

The two homeless friends who are the spotlight of this article series, Dale Malone, 59, and Leroy Conner, 64, want to get off the streets and into an apartment. But to get government housing vouchers in Texas, they need to show photo IDs (which both have lost). Even if they landed full-time jobs and wanted to pay for the apartment themselves, most leasing offices would still require them to show a photo ID.

Basically, without IDs, they can’t get an apartment. But without a residence address, they can’t get photo IDs.

Or, let’s say they apply for full-time jobs. In the United States, an employer is legally required to check a prospective employee’s photo ID. Without photo IDs, Dale and Leroy can’t get official full-time or part-time jobs. But without a job, it’s hard to afford an apartment. And without an address, they can’t get IDs. And without IDs…

You get the idea.

But what if they could save up money for an apartment by doing odd jobs, recycling, panhandling, or wielding squeegees? If they tried to hide the money in their wallets, backpacks, or sleeping spots, someone would probably steal it—something Dale has already experienced many times. That’s how life on the streets works.

To really keep the money safe, they would need to open bank accounts. But the bank is legally required to—you guessed it…

Check their photo IDs.

A similar Catch-22 happens with various identification documents. To get a driver’s license or Texas ID, you need documents like your birth certificate or social security card. But what if you lost those? Well, to get your birth certificate, you need your driver’s license or social security card. And to get your social security card, you need your birth certificate or driver’s license.

There are ways out of these Catch-22s. To substitute for a missing document, you might be able to provide an immunization record, school record, or voter registration card, for example. These are called "supporting identification documents," and Texas DPS has a long list of them.

But if you don’t have a safe place to store your belongings, you probably don’t have many (or any) of those documents, either. And if you don’t have a residence address, a phone, or a car, tracking down those documents is a pain. It requires finding the right government offices, making appointments, making it to appointments, asking the right questions, being persistent, and knowing the ins and outs of the system.

That’s where Operation ID comes in.

Located downtown on the property of First Presbyterian Church, Operation ID supports sixty-eight partner organizations in their efforts to help homeless people, human trafficking victims, domestic violence victims, vulnerable youth, and more.

Among these populations, lack of identification is a startlingly common problem. Personally, I can’t recall meeting a single homeless person who hasn’t lost their ID at some point, often due to theft.

That’s why Operation ID focuses on one thing: helping people without IDs or birth certificates get them. They serve anyone who was born in any of the fifty states or U.S. territories, as well as U.S. citizens who were born overseas (such as children of military members).

Op ID’s “street cred” is legendary. Ask any homeless person in Houston if they’ve heard of Operation ID, and four times out of five, the answer will be yes. Most of the homeless people I know (at least downtown) have been assisted by Op ID at some point, and they mostly have positive things to say. Many of them have now been moved into housing.

Operation ID’s reputation overshadows that of its parent organization, Main Street Ministries, at least according to MSM’s executive director Barbara Allen. (MSM also has a Life Empowerment program to help housed individuals out of poverty.)

Wearing a tan jacket, Allen sat down with the Op ID program manager, Cathy Ode, so they could explain how the program operates.

Before COVID, Ode said, they would have 50-70 people waiting outside every Tuesday and Thursday morning, hoping to be lucky enough to make it inside. Some would sleep outside the door.

"We didn't know who was coming in, what to expect for volume, or any of that," said Ode. Back then, the process of helping each client usually took two to two-and-a-half hours.

During COVID, they rethought their policies. In Ode's words, "If they can make it to a doctor's appointment, why can't they make it to...an appointment for local documents?"

So, they switched to an appointment-only system. Allen thinks that's more meaningful to clients: "There's a volume of difference between waiting in line with 75 people as opposed to 'Welcome, Mr. Smith. You're here for your nine o-clock?'"

Clients are seated in a room with five spaced-out desks. Volunteers bring them packets with important documents. Then, using a pair of headphones and a tablet, each client will FaceTime with a volunteer who walks them through the process of filling out their applications.

Now, it only takes around fifteen minutes for a client to walk out the door with a completed application and a check to the DPS, says Ode. (For out-of-state birth certificate requests, the process may take up to twenty-five minutes.)

To get assistance from Op ID, people need to be referred by one of Op ID’s partner agencies. Allen says that’s because these organizations provide case managers who have personal relationships with the clients and already know important information about them. If a client does not have a phone or email of their own, the case manager can also help with that.

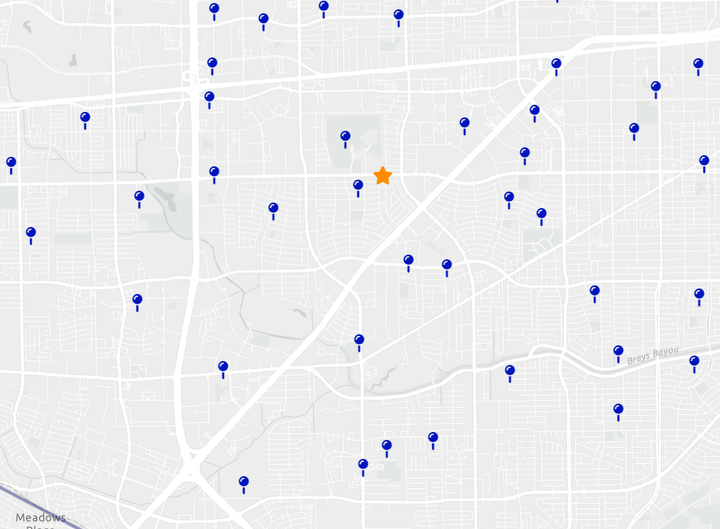

The challenge is, most of these partner organizations, like Operation ID, are clustered downtown, forty-five minutes to an hour (or more) away from Sharpstown by bus.

But one partner agency, Christian Community Service Center, is in Sharpstown on the campus of St. Luke’s United Methodist Gethsemane. CCSC doesn’t primarily focus on serving the homeless, but they do make referrals to Op ID.

HPD’s Homeless Outreach Team (HOT) and HCSO's Homeless Outreach Team (also HOT) also makes referrals to Operation ID and visits southwest Houston. Leroy says he’s been in contact with a HCSO HOT officer.

Another referral agency, Healthcare for the Homeless, visits southwest Houston every few months, according to associate medical director Mudit Gilotra.

Overall, though, there are much fewer services for the homeless in southwest Houston than downtown.

Due to a shortage of volunteers, Op ID is also serving fewer people than Allen and Ode hope to in the future.

On Mondays and Wednesdays, volunteers meet virtually with qualified clients (like domestic violence victims, who may not be able to travel without being tracked by their abusers). On Tuesday and Thursday mornings, Op ID sees an average of ten to fifteen clients in person. But Ode says their facility has room for more.

They want more volunteers who are interested in things like greeting clients at the door, conducting phone interviews, meeting with clients for in-person appointments, corresponding with jail inmates who need to prepare for release, and answering the forty to fifty voicemails that Op ID finds on the answering machine every Monday.

One volunteer, Ed, says that they need more admin volunteers like him to process paperwork behind the scenes. “There’s a lot of chasing after paper here.”

Volunteers have quite a bit of freedom to choose roles, said Cathy: “We want people to do things they enjoy doing.”

Ed says he chooses to come in for six hours a week, sometimes more. Why?

As he put it, “These are real live people that really need help.”

Correction: in the earlier version, I said that Leroy got his homeless ID from HPD's Homeless Outreach Team (HOT). Actually, he got it from the Harris County Sheriff's Office's Homeless Outreach Team (also HOT). I didn't realize that there were two different HOT's. (And don't confuse them with Council Member Edward Pollard's HOT team that cleans up illegal dumping in District J!) My apologies to HCSO for failing to give them due credit earlier.

Subscribe for free so you don't miss future articles in this series, where I follow Dale and Leroy in their quest to climb off the streets of Sharpstown. You can read Part 3 here.

Conflict of Interest Statement: If you've been following this series, you know I take a personal interest in this story. I've known Dale and Leroy for a while (Dale for four years). That's why I used their first names instead of following the standard journalistic practice of using last names. I'm taking a more personal approach for this series. Both men have also attended my church—Dale on a semi-regular basis. Finally, several Christian friends and I are involved in an unofficial homeless ministry that meets on a weekly basis, and we often speak with these two men.

Comments ()