Finding Refuge in Sharpstown: A Young Woman’s Journey from Thailand to Texas

Martha Mathew knocks at the yellow door of an apartment near Ranchester and Bellaire. As I wait behind her, we slip off our shoes and place them next to the others lining the concrete step.

A young woman with a shy smile opens the door and welcomes us in.

War drove Elizabeth Poe and her family from a bamboo hut to this apartment when she was nine years old. Now 24, she lives with her father and two brothers.

Poe invites me to sit on a couch in the corner of the room, beneath pictures of her family. Across the room, a candle burns next to a painting of Jesus, which looks back at me.

Several years ago, Mathew taught ESL classes to refugees in Sharpstown, including Poe’s family, who are Karenni.

The Karenni are part of the Karen ethnic minority group that lives on the eastern border of the country of Myanmar, formally known as Burma. When Burma received its independence from Great Britain, the Burmese government included the Karen State within their borders. The Karen sought independence, but were instead met with decades of violence and war from Burmese military, police, and citizens.

“The Burmese would go to a village and force the people into slavery,” Poe shares. “They would rape the women, steal the people’s food, and beat men if they refused to give them what they wanted.”

It’s no surprise that many of the Karenni people would flee whenever they heard the Burmese troops were coming.

For years, Poe’s father fought with the Karenni resistance, but when he married Poe’s mother, they decided to flee to a refugee camp in Thailand not far from where they lived on the eastern border of Burma.

But even in Thailand, life for Karenni refugees wasn’t easy. Though they did not have to fear losing their belongings or being taken as slaves, they faced other challenges, especially lack of employment. The refugees were not allowed to leave the boundaries of the camp or have jobs—except for a few women who were able to find work as maids in Thai homes, which was considered an acceptable job for a refugee.

Without employment, Poe and her family were solely dependent on the rations that United Nations workers brought once a month: rice, oil, mung beans, and sometimes dried pepper. The Karenni refugees would try to plant vegetables to sustain their families in between ration deliveries, but it was a difficult task in a crowded refugee camp.

Some even resorted to hunting birds or foraging for bamboo, cucumber, and anything else they could find near the camp. “A lot of people went out to the mountain to try and find food,” Poe recalls. “Sometimes they would steal from nearby farms owned by Thai families.”

The camp community was divided into numbered sections, each with its own communal bathroom, which also served as a storage facility for drinking, cooking, and cleaning water. There was no electricity, and mosquito nets were essential during the rainy season.

Education was another challenge in a refugee camp that was only meant to be a temporary solution for housing (though this often turns out to not be the case).

“My parents wanted me to learn about God, so they sent me to St. Mary’s, a Catholic School near the camp,” Poe explains. “It was a twenty minute walk from where we lived, and I had to travel up two hills because we lived in a valley. When it was the rainy season, and I was late to school, I would slip and fall.”

Poe only attended school there for first and second grade before her family was sponsored by the United Nations to move to the United States. Before moving, they were given some lessons in English and American culture, but very little.

“We were taught the English alphabet and numbers, and they did have a training for living in America,” Poe shares, “like how to greet people and use the bathroom because they’re different here.”

Their family was grateful for the opportunity, but Poe also recalls the struggle of moving to an entirely new country and culture: “It was hard. A lot of it was that we didn’t know any English or where things were. We were told we had to get an immunization shot, but we didn’t know where to go.”

When they arrived in the States, their case worker and some friends who had already arrived were there to greet them. Soon after, Poe’s family settled in the apartment where they still live today.

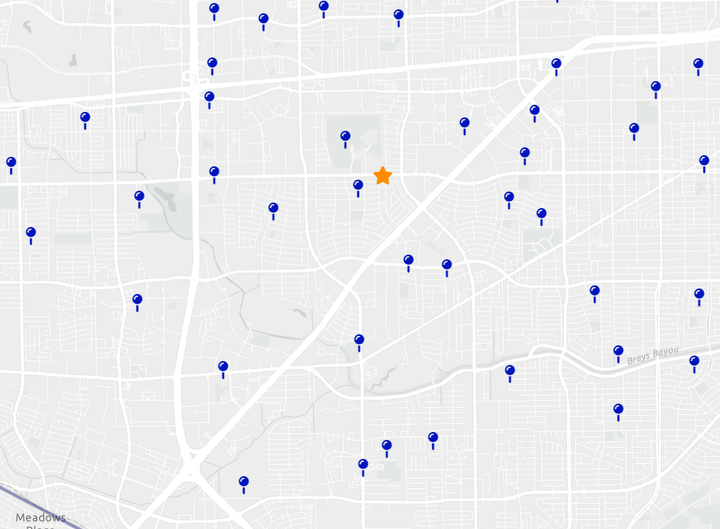

Chinatown at the corner of Ranchester and Bellaire in Sharpstown where many refugees are resettled

Poe and her two younger brothers were enrolled in a local public school. Throughout elementary, all the refugee students, including Karen, Karenni, and Burmese children, were placed in one ESL class.

Poe went on to graduate from Elsik High School in Alief ISD and obtain her dental assistant certificate from Houston Community College. Without a car, it was a 45-minute bus ride from her family’s apartment to HCC’s campus, but she was determined. She now works full-time as a dental assistant in Chinatown.

As we talk, an older man, thin yet strong, walks by us toward the kitchen. He reaches out to straighten something on the mantelpiece with the one hand he has left.

“My father was in an accident at work,” Poe explains for him. “He was climbing a metal pole and was struck by lightning. They had to amputate his arm, so his work paid for the medical expenses, his prosthetic arm, and our rent for five years.”

Though she has applied for medical disability on behalf of her father, their claim was denied.

“The government says he can work, but my father’s job was manual labor,” she says sadly. “He does not have an American education, and he can’t do manual labor any more. We are trying to appeal the claim.”

With her father disabled, and his old company no longer paying the rent, the responsibility now lies on Poe and her brothers to pay the family bills—and support the family in other ways.

“Our parents still rely on us,” she shares. “When they have an appointment, we have to take them and translate. Things are much better now than when we first moved, though, except for the language.”

Many Americans assume that refugees and immigrants desire to live in America, but this is not always the case. Refugees are grateful to have a safe place to live, but it is far away from everything they know.

“A lot of the older people don’t like it here,” Poe admits, “because they’re farmers and they can’t do that here.” When asked why, Poe replies, “The land here is too expensive. Over there, they would just build a house wherever they wanted.”

But Poe has a different perspective on life here in Sharpstown, Texas.

“There is definitely more opportunity here than in Thailand because we couldn’t leave the camp,” she says. “Here we can buy a house, get education, and have jobs.”

After all the difficulties Poe has faced, Sharpstown is a land of opportunity. Her dream is to one day own a home with her family and become a dental hygienist. For Poe, there is hope for the future.

Author

Assistant Reporter

Martha Mathew

Comments ()