Harris County Building Gates to Keep Bissonnet Track Closed

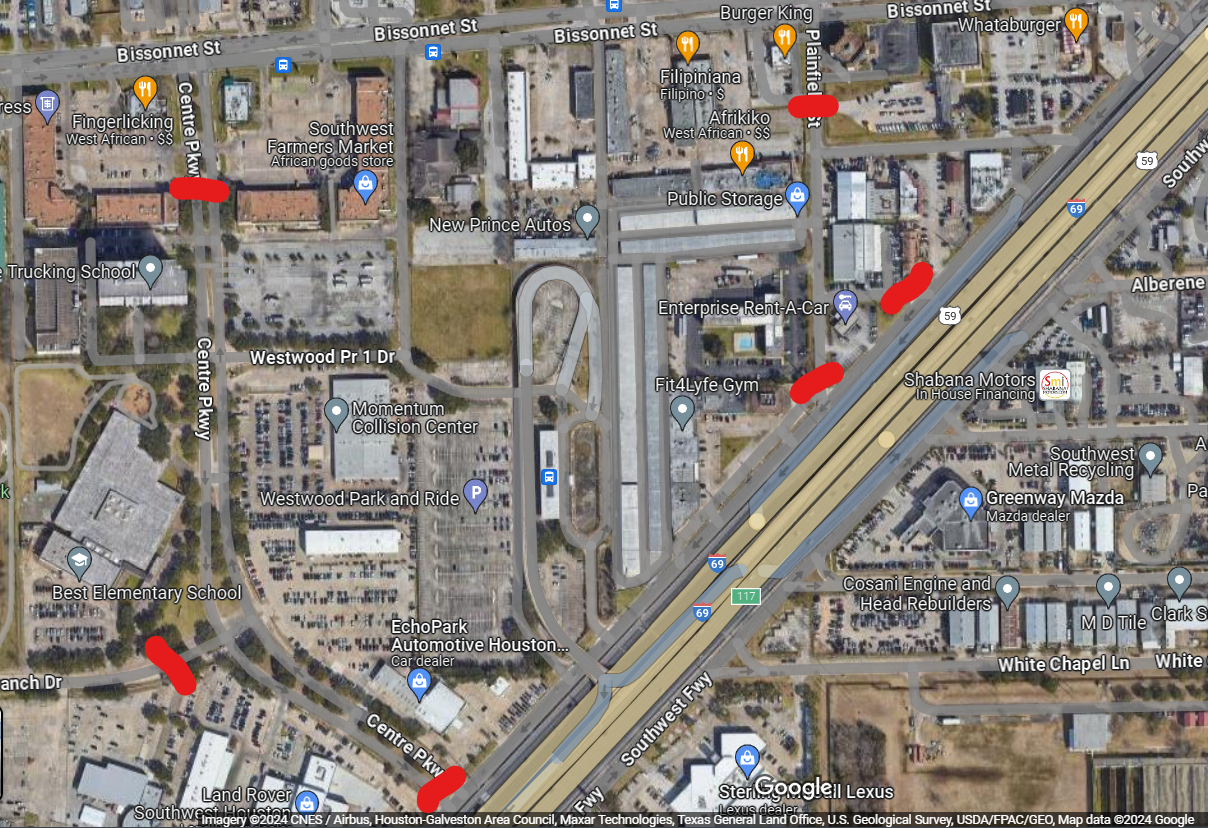

Update: As of 2/9/24, swing gates have been installed in all six locations, and the upright posts have been painted white.

Visit the infamous “Bissonnet Track” today, and you wouldn’t guess that just nine months ago, it was a hub for open-air prostitution—day and night.

On the drizzly night of January 23, 2024, just before the hard rain hit, the west side of the Track was quiet.

In hopes to keep it that way, Harris County Precinct 4 Commissioner Lesley Briones’ office is constructing yellow swing gates to close two streets nightly. Gates are already complete at three out of six road locations, with construction slated to be finished by the end of January.

This will be cheaper than the previous solution, which was effective but financially unsustainable.

The recently installed swing gates at two ends of Plainfield St on the Bissonnet Track

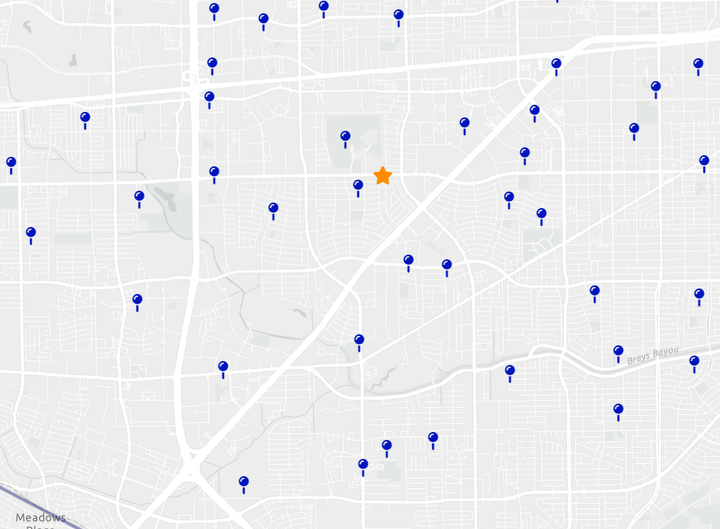

Southwest Houston's Bissonnet Track is a circuit with four segments: parts of Bissonnet St, Plainfield St, the 59 frontage road, and Centre Pkwy. In the past, johns would drive around the circuit to pick from the dozens of prostitutes who crowded the area. Kids on their way to nearby Best Elementary would see prostitutes soliciting in broad daylight.

For years, nonprofits like the Landing and Elijah Rising have worked to help women in the area, many of whom are victims of sex trafficking. But in the meantime, local government wanted the concentrated, open-air prostitution out of the area.

After trying several tactics to no avail, HPD, the Houston City Council, and Harris County Precinct 4 settled on a simple solution: have police officers set up and man barricades on Plainfield St and Centre Parkway every night. Pimps, prostitutes, and johns couldn’t circle the Track anymore. It also meant there was a strong, nightly police presence in the area.

Soon, almost all the blatant, open-air trafficking on the Track dried up (although much sex trafficking in 2024 is stealthier, happening on social media and the internet).

But the solution was expensive: as of June 9, 2023, the blockade was costing ~1,400 per night in officer overtime. District J Council Member Edward Pollard said that he was considering other options for the long term.

Now, as part of a collaborative agreement, Harris County Commissioner Precinct 4 is constructing the yellow swing gates. According to Syan Rodes, HCP4’s press secretary, an HPD officer will manually close and lock the gates each night at 10:00 PM and open them each morning at 5:00 AM. That way, the city doesn’t need to pay officers overtime to man the barricades all night.

Peter Acquaro, head of the Southwest Management District’s Public Safety Committee, added that the locking and unlocking will keep a consistent police presence in the area.

But what if people drive through the gates and damage them? “That’s where we step in,” said Acquaro. The Southwest Management District has agreed to take responsibility for maintaining that gates once they’re constructed.

According to Rodes, HCP4 paid $15,000 for the gate materials, and is designing, building, and installing the gates “in-house.” That’s much cheaper than the $250,183 that the nightly blockades cost in officer overtime in 2023, according to data from HPD's Open Records Unit. (The blockades began on May 16.)

What do local business owners think?

Inside Finger Licking, a West African restaurant, manager Bola Remi said the shutdown of the Track hadn’t affected the number of customers who visited. At 7:00 PM, most of the cream chairs in the large dining room were empty (but it was a Tuesday night).

She had seen the gates go up near the Burger King on the other end of the Track, and overall, she thought that the police efforts were “a good idea.”

Before the shutdown, she said, prostitutes were “basically roaming the streets.” Now, “It’s been nice, quiet—no trouble.”

Inside tiny Kim Café, which hangs onto the skirts of a strip mall behind Finger Licking, owner Alan Lai spoke over the sizzle of wings and rice from the kitchen as he packed three takeout boxes into a brown paper bag. The fifteen chairs in the dining room were empty.

He said that many of his old customers left in July and August, and he wasn’t sure why, but new customers have been coming.

He hadn’t heard about the swing gates, but he said that the police blockade has “helped the community”—“Before that, it’s a lot of chaos… Right now, it’s better.”

But as David Gamboa, communications director for Elijah Rising, said in June, “It's likely [the women] are still being trafficked either online and in hotels, in strip clubs, or in another city.”

The gates may keep the trafficking out of the neighborhood, but they will probably not get the victims out of trafficking.

Where are the victims now?

Comments ()