From War to America: Vietnamese Americans Share Stories at the New Houston Vietnam Veterans Memorial

During his seven-year term in a communist “re-education camp,” the only food Dong Nguyen received was one small bowl of rice per day.

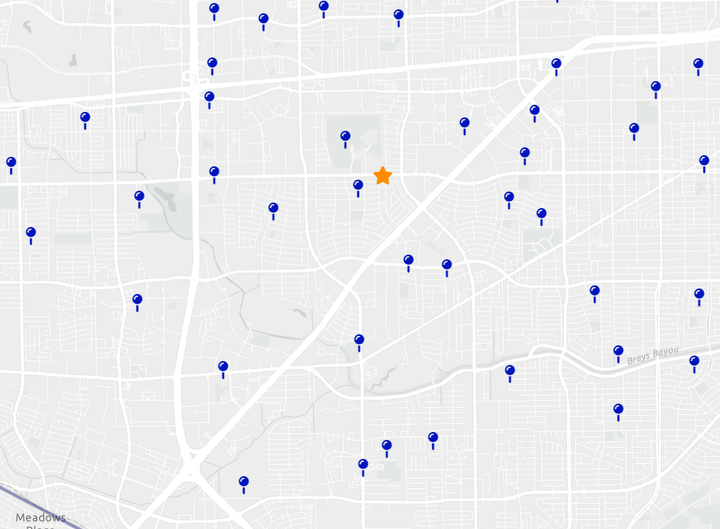

That’s the story he told on a quiet, 82-degree Memorial Day morning at the new Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Club Creek Park. Dong and his wife, Nhung, had just met Stan Wesolowski, a Sharpstown resident and U.S. Army veteran who served in Vietnam. Soon, Dong and Stan were swapping stories about the war and its aftermath.

Dong is not the stereotypical Vietnam veteran. The usual image would be a teenager who got shipped from America to southeast Asia to hack his way through mosquito-infested jungles while watching for ambushes.

But there is another kind of Vietnam veteran, one that Mayor Sylvester Turner and District J Council Member Edward Pollard honored in the unveiling ceremony for the memorial on Friday, May 26th, 2023. Both credited America’s South Vietnamese allies, who fought and worked side by side with American soldiers against the communist North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC).

Dong was one of America’s allies: he served in the South Vietnamese Air Force. He didn’t fly, but he directed a “political warfare” project, which used propaganda to boost South Vietnamese morale and encourage NVA soldiers to defect.

When South Vietnam fell to the NVA, some members of the South Vietnamese military were able to escape from the capital, Saigon, to America. But Dong, stationed in the city of Can Tho, was not able to make it to Saigon in time. Since he had aided the Americans, the conquering NVA put him in a “re-education camp.” Of course, Dong said, that really meant “prison.”

Hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese were sent to such prisons, which author Doan Van Toai compared to the infamous Soviet gulags. Those who served in the South Vietnamese military or government were at risk—unless they could escape the country.

Loc Bui's Story

Loc Bui, another member of the South Vietnamese military, was at Saigon when it fell. He watched from a navy ship as the NVA fired rockets on the city.

Forty-eight years later, after the unveiling ceremony at Club Creek Park, he sat in an otherwise empty row of folding chairs, eating a cookie. He sported a salt-and-pepper mustache, a military cap, and a belt buckle that displayed an American flag flanked by eagles. What follows is the story he told.

Years before the fall of Saigon, Loc served as an interpreter for the Department of State and the U.S. Navy at Nha Be, a district of Saigon. As a bilingual radio man, he worked in the control room of an operation center, helping with tasks like dispatching helicopters for medical evacuations. The U.S. military also trained him with weapons, sonar, and engine repair.

When the American soldiers withdrew from Vietnam in March 1973, they left the South Vietnamese military to continue the fight against the North. Loc became the captain of a PBR (Patrol Boat, River) in his country’s navy. He clarified that he did not hold the official rank of captain—he served at the Vietnamese equivalents of ranks E-4 and E-5—but “captain” was just his job description. “Like the way you call a truck driver ‘truck driver,’” he said.

Mazes of rivers snake through the Vietnamese jungle. His boat would patrol a river for three weeks, then rotate with another boat crew and move to another river. Sometimes, they patrolled during the day; other times, they would perform what he called “the night ambush.”

He and his crew would put color on their faces to blend in with the darkness. After being given coordinates, he would navigate there, cut the engine, and hit the river bank. Then, they waited.

They watched for communist fighters moving in the darkness. If they saw a small group, they would attack. If they saw a large number of enemies, Loc would radio the enemy’s coordinates to a friendly base and call in a strike. “Five rockets,” he said.

But night ambushes were not enough to hold the NVA and VC at bay. Eventually, communist forces pushed deep into South Vietnam and attacked Saigon.

On April 30th, 1975, Loc and his wife waited on a navy ship in the harbor of Saigon as NVA tanks rolled into the city. He said that everyone on the ship was crying—including him.

They weren’t just mourning the conquest of their home. Many were worried for relatives they were leaving behind. Loc had two brothers who were staying.

The president of South Vietnam, Duong Van Minh, surrendered, ordering his troops to put their weapons down. But a navy commander* had other ideas. At 6:00 PM, the commander ordered several ships (including Loc’s) to leave.

“Nobody knew what was going on, nobody knew where we were going,” said Loc.

The captain told them that they might come back in one or two months once things calmed down. For Loc, those one or two months became forever. Their ship sailed to the Philippines, where he boarded a plane to Pennsylvania as a refugee. Now, he lives in Bellaire and works at a chemical plant.

He said, “I want to go back when they have freedom…democracy, human rights, and equality.” But not now. “Communists don’t care who you are—they kill you.”

Left to right: Dong Nguyen as an Air Cadet in 1966; Loc Bui at the memorial dedication ceremony; the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Although Loc escaped, his brothers were not so fortunate. Before making it to the United States, one endured thirteen years in the infamous “re-education camps.” The other endured six-and-a-half years.

Like Dong Nguyen, did they only eat one bowl of rice a day? Their menu may have had some variety: Dong said that sometimes, if there was no rice, he received an equivalent weight of cassava.

If their experience was like Dong’s, they also had little contact with family.

Dong Nguyen's Story, Continued

When Dong went to prison, he had a five-year-old son—and another son in his wife’s womb. He wasn’t allowed to see them for five years. Whenever he wrote a letter home, a communist censor would read it first to ensure that he wasn’t saying anything bad about the prison. Whenever his wife wrote back, the censors would open the letter and read it before he did.

When his family was finally allowed to visit—after five years without him ever meeting his second son—a police officer sat between him and his wife, Nhung, to listen to their conversation.

In 1982, he was finally released. “Freedom” meant returning to his house and not being allowed to leave without the permission of the police. Like many of the famous “boat people,” he tried to escape Vietnam illegally on a small boat, but he was captured and almost spent more time in prison.

Later, though, the U.S. and Vietnamese governments made a deal: any South Vietnamese veteran who had endured three or more years in prison could come to America as a refugee. So Dong, Nhung, and their now three sons boarded a plane to Chicago in 1992. Then, they came to Houston, where Dong worked as a lathe operator at Kemlon until retirement. They eventually settled in Brays Oaks, but their youngest son attended Sharpstown High School.

Now, Dong and Nhung have been married for fifty-three years and have six grandchildren. One son is a civil engineer, one is an IT specialist, and one works in quality control at Schlumberger. Nhung proudly showed pictures of her family.

Nhung went on to write six books in Vietnamese, including one about Dong’s story. One book, Buc Tranh Theu Ban Do Nuoc My, appears to detail their travels across Vietnam, Europe, and America (based on an English translation of the Amazon preview).

Looking at Dong, with his polo shirt, sunglasses, and somehow-youthful-looking shock of grey hair, one would never guess that he spent seven years underfed in a communist prison. Looking at Nhung, with her elegant purple shirt and green heart necklace, one would never guess that she spent seven years separated from her husband, raising two boys on her own. Both smiled and laughed; both had youthful complexions (it would be impossible to guess their ages).

Unlike Loc Bui, they took seventeen years to escape from the communist regime that conquered South Vietnam. And yet, by all appearances, they have carved out a good life in America. The family pictures testified to their quiet resilience, their patient labor.

Perhaps it has something to do with their Roman Catholic faith. Or perhaps they are just strong individuals. Or perhaps they still carry hidden wounds.

But there are some souls that prison cannot break.

—This story has been updated to reflect that one of Dong and Nguyen's sons attended Sharpstown High School and one works at Schlumberger.

*This commander was probably Captain Kiem Do, whose book Counterpart describes how he evacuated approximately 30,000 men, women, and children to Subic Bay using thirty-five ships.

Read more about the memorial and the dedication ceremony here:

Author

Tyess Korsmo, the Sharpener's editor-in-chief, moved to Sharpstown in 2019 to earn his Master of Liberal Arts at HCU, where he now teaches English and history. He also teaches English in a maximum-security prison.

Did we make a mistake? Please let us know at sharpstownsharpener@gmail.com.

Comments ()