Being Carless in Sharpstown

I didn’t pay much attention to public transportation—until somebody hit my car and messed up my transmission.

I didn’t have the time (or budget) to go car shopping right away. I was wrapping up a semester of teaching five college classes, preparing to teach a summer class in a maximum-security prison, and preparing to launch the Sharpener.

Without the money to Uber everywhere, I was left with four main travel options: walk, bike, take the bus, or bum rides off of friends and coworkers.

Through a hectic combination of the four, I was (barely) able to get everywhere I needed to go. But the experience taught me that living in Sharpstown without a car is a royal pain.

One of my teaching jobs was in Sugar Land. There are no buses between Sharpstown and Sugar Land. The bike ride would have been forty-five minutes, 8.5 miles, and sweaty. I didn’t feel like showing up to work smelling like a wet dog.

Solution? Ask my friend and colleague to make a twenty-minute detour to take me to work with him. Fortunately, he was kind enough to do it more than once.

Another one of my teaching jobs is at the Memorial Unit in Rosharon. The only buses that run down there are prison buses, and I didn’t feel like robbing a store just to earn a free ride. (Unfortunately, it would have been a one-way ticket.)

Solution? Check the class schedule to find out which of my colleagues would be teaching each day that I taught, then find out which ones could pick me up without making a massive detour, then ask them. Again, fortunately they were kind enough to oblige me. The Uber trips would have cost $30-40 each way.

Another one of my teaching jobs is at Houston Christian University, right here in Sharpstown. Okay, at least that one was close. But still, what should have been an eight-minute car ride from my apartment would turn into a twenty-six-minute combination of walking and riding the bus (and that’s if I didn’t have to wait for the bus, which could take ten minutes or more to arrive).

It would have actually been twice as fast to bike there (if I didn’t mind showing up to class smelling like a wet dog).

Neither option was ideal, but at least I had two viable ways to get there. At least there was a bus.

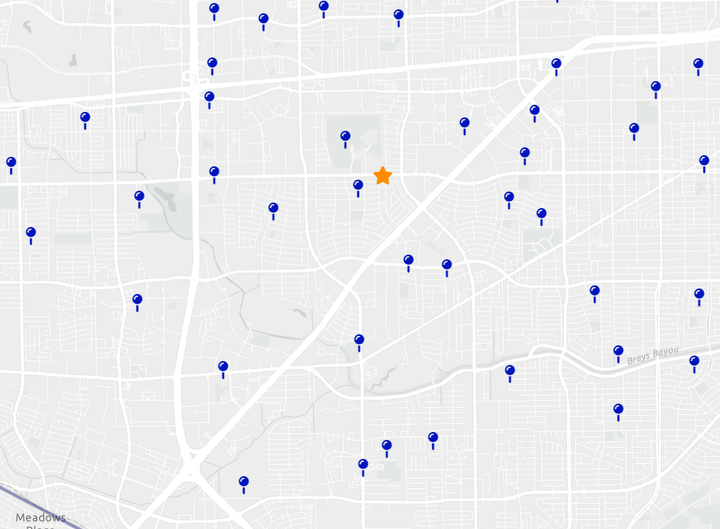

And then came the reporting. Suddenly, I had to travel to almost every corner of Sharpstown to attend meetings and interview people.

The good news? I’m reasonably in shape, so I can bike to pretty much anywhere in Sharpstown in twenty minutes or less.

The bad news? Biking was still slower—and hotter—than driving. I showed up to the TIRZ #20 meeting in Chinatown two minutes late, sweaty, and breathing hard.

And I couldn’t carry anything more than what would fit in a backpack. I still had to take the bus to get groceries.

Well, technically, there are two grocery stores within a fifteen-minute walk from my apartment, but they tend to have higher prices on some items. The La Placita in my neighborhood has good deals on onions and bulk dry beans, but last I visited, their eggs were almost three times the price of ALDI’s.

Did I survive being carless? Yes. Did my ancestors have to travel everywhere on foot and horse-drawn carts? Yes.

But back then, life was built for walkers and cart riders. Now, at least in Houston, life is built for car owners.

My experience made me appreciate how much more challenging life can become for people without cars in Sharpstown—especially if they are elderly or disabled, if they have young children, or if they’re not an early-twenties guy with energy to burn. Many people are stuck taking the bus, which is just plain slow. (At least disabled people also have the option of METROLift, although I’m not sure how fast that is.)

Many METRO routes only run once every half hour. Even for the highest-frequency routes, riders may have to wait up to ten minutes for each bus—and some trips require making one, two, or even three bus transfers each way.

When everything takes longer—even basic things like getting to work, buying groceries, attending church, getting to the laundromat, and attending community meetings—it’s crazy how quickly the hours can burn away.

It hit home when I taught at the High School Writers’ Institute at the University of St. Thomas in Montrose (west of downtown Houston). I had been asked to show up at 8:30 AM, thirty minutes before students arrived.

Google Maps told me the bus ride would take about fifty minutes. I marched up to the bus stop at 7:40 AM, two minutes before the bus should have arrived, but it was delayed by seven minutes. Then, when I got to the Texas Medical Center Transit Center, I had to transfer and wait ten minutes for anotherbus. Both buses also got stuck in traffic.

I ended up arriving at 8:55 AM, five minutes before the first day of camp began. Not a great first impression.

The rest of the week, I decided to assume the buses would be late, so I arrived at the bus stop extra early. From then on, I made it to camp early—usually around 8:20. But to be safe, I had to budget seventy-five minutes of travel time—just to get to the west side of downtown. (And don’t forget the trip back.)

Now imagine if I had to travel to the north side of downtown to deliver a public comment at a City Council meeting.

This is why METRO plans to improve local bus travel through projects like the controversial Gulfton Corridor extension of the Silver Line. Right now, relying on public transportation in southwest Houston is difficult.

After all, Houston was designed for the car, not the bus. Frank Sharp originally built Sharpstown as a middle-class suburb for car-owning commuters. Now that Sharpstown only has a median household income of approximately $37,000 (based on a 2019 estimate), and Houston’s massive population growth is clogging our freeways anyway, public transportation advocates argue that it’s time to upgrade our city’s bus and rail systems.

Understandably, many local car drivers worry about how the Gulfton Corridor extension may reduce local traffic lanes. (Some folks, mostly libertarian types, even argue that public transportation shouldn’t exist—it’s not government’s job.) I’m also worried, based on my recent Silver Line trip, that these “METRORapid” buses may not be everything they’re advertised to be. And, of course, the project would spend a lot of American taxpayer money—always something to think twice about.

But before judging METRO’s projects too harshly, car drivers should also learn to see this issue from another perspective—by stepping into a pair of shoes that doesn’t own a set of wheels.

Comments ()