Climbing off the Streets, Part 5: One Step Closer

"I was here earlier and I needed one more document to get my stuff done," says Dale Malone, 59, to a male employee inside the front door of the Rosenberg DPS.

Dale is trying to get a replacement copy of his driver's license—his gateway to society—after his old one was stolen. It would be an understatement to say it's been a challenge.

It's 4:30 PM, and we’re hoping there won’t be a crazy line. If we can’t get his license before closing, we’ll have to make another appointment—one more delay in Dale’s quest to get off the streets of Sharpstown and into housing.

The employee replies, “Go to the same station." We don't even have to wait.

Dale strides to the whitish-gray cubicle where, four hours earlier, an employee told him her manager wouldn’t accept his METRO disability ID card as proof of identity.

The woman behind the desk looks up. Her eyes widen in pleasant surprise. "Welcome back, you guys!"

Dale hands her the copies of his Social Security card and old driver’s license that True Mental Health Services gave him half an hour before.

The woman’s face falls. “A photocopy doesn't work.”

I pipe up. While sitting in the waiting room at True Mental Health Services, Dale and I had been trying to figure out how to set up an app to access Dale’s electronic insurance card (another possible identifying document) on his new phone.

At 58, he’s not very handy with newfangled tech, so he had been under the impression that to download apps from the Google App Store, he needed to provide a credit or debit card number (something he didn’t have). He didn’t realize that when the App Store requested payment information, he could just click “Skip.” (He also has vision problems and often loses his glasses.)

Once we cleared that hurdle and installed the app, we tried to set up his insurance account, but we hadn’t finished before we left True MHS.

Now, I tell the woman that if Dale's METRO ID card and the copies of his social and driver’s license won’t work, we can try to finish setting up the app so we can show her his electronic insurance card.

She takes the METRO ID and his other papers. "Go ahead and continue working on that, and I'll see what I can do."

She leaves to talk to her manager for the second time that day. Dale says a quick prayer.

We've almost finished with the app when she returns, smiling. “They approved it."

Dale is so focused on writing down his insurance password that he doesn't seem to hear right away. But when she asks to take his picture, he's hamming it up. "Man, I'm glad I just cut my hair and everything.... Can I have a hat on?"

"No hat," she replies.

"I knew better," he says. "I'm proud of my hat."

She gives him a temporary paper copy of his new ID and says that the hard copy will be mailed soon.

But there's one catch: he'll have to return by December to renew his license, and this time, he'll need his birth certificate.

On the way out, he speaks to the blonde employee who originally told him that his METRO card was an acceptable form of ID. She says she double-checked and she still thinks it should have counted, but either way, she's glad he got approved.

Outside, Dale is moved. "I ain't gonna start cryin' on you man... I can't help it though, man."

After years, Dale and his friend Leroy Conner finally have state-issued photo IDs.

But this is just the first step to getting off the streets. Now they won’t be automatically denied when they apply for an apartment, job, housing voucher, or bank account. But it doesn’t mean they’ll automatically succeed, either.

As anyone who has applied for a job knows, a photo ID is the bare minimum. Potential employers will take plenty of other factors into account.

Despite being six years older, Leroy is the fitter of the two, and he’s already landed an unofficial security job that comes with a place to sleep, at least for now. But it's still not a full reentrance into society.

Meanwhile, Dale says his doctors tell him he’s unfit for work due to his COPD and multiple strokes, although he still wants to start his own business.

Anyway, it’s difficult to get and keep a job without getting housing first. Employers generally don't appreciate un-showered employees, for one thing. And it's hard to get a good night's sleep on the streets.

For now, Dale might have better luck opening a bank account so he can receive his government disability check again, then applying for a government housing voucher to supplement it. But he also needs to find an apartment that will accept a tenant with a bad credit score.

In the meantime, he needs to get his birth certificate and social security card, then hang on to all of his documents. If they get stolen again, he could be back to square one.

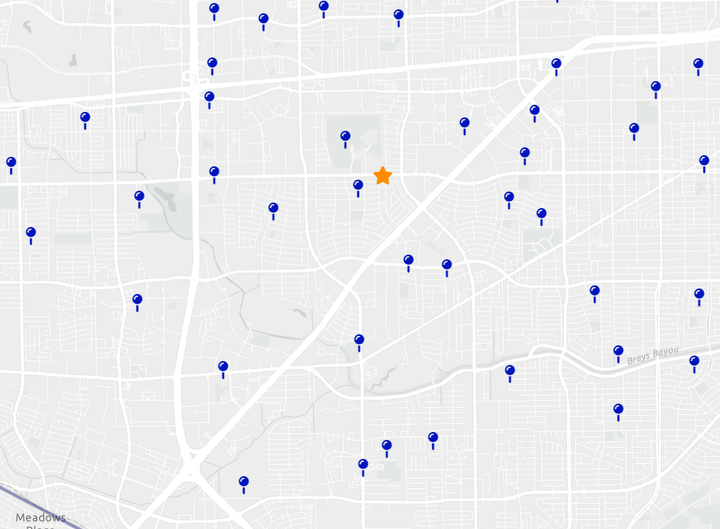

But for now, Dale and I are both hungry. During our wild journey to Rosenberg, then Gulfton, then Sugar Land, then Mid-West, then Rosenberg again, we never managed to eat lunch. We were too occupied with tracking down the documents he needed to get his ID.

Actually, since he was asking for a replacement, not a renewal, he only needed one document. That was hard enough.

But neither Dale nor Leroy would likely have got an ID without help. And I’m not talking about my help.

Leroy only had his documents because Operation ID and the Harris County Sheriff's Office’s Homeless Outreach Team had helped him get them last summer.

Dale was only able to get the copies of his social and driver’s license because True MHS had helped him get his ID years ago (which is probably how he got his METRO disability card, too). And I wouldn’t be surprised if True MHS received help from Operation ID. When I visited Op ID, Executive Director Barbara Allen told me that both Dale and Leroy were in Op ID's database.

True MHS also helped Dale get his health insurance–our fallback identification option.

Not to mention that Dale's sister had helped him in the past and was the one who pointed us to True MHS.

Not to mention that Leroy encouraged Dale when he was ready to give up.

Not to mention that overall, despite some hiccups, the DPS employees were fairly friendly and helpful. (But dealing with them did require some persistence.)

For Dale or Leroy alone, the odds would have been dire. Fortunately, they have support—including each other.

Now for the next steps—but at least we finished the easy part.

Correction: in the earlier version, I said that Leroy got his homeless ID from HPD's Homeless Outreach Team (HOT). Actually, he got it from the Harris County Sheriff's Office's Homeless Outreach Team (also HOT). I didn't realize that there were two different HOT's. (And don't confuse them with Council Member Edward Pollard's HOT team that cleans up illegal dumping in District J!) My apologies to HCSO for failing to give them due credit earlier.

Subscribe for free so you don't miss the next article in this series, where I follow Dale and Leroy in their quest to climb off the streets of Sharpstown.

Miss the first article in this series? Read it here.

Conflict of Interest Statement: It should be obvious, but I take a personal interest in this story. After all, I drove Dale and Leroy to Rosenberg. I've known them for a while, especially Dale (I've spent countless hours in conversations with him over the last four years). That's why I used their first names instead of following the standard journalistic practice of using last names. I'm taking a more personal approach for this series. Both men have also attended my church—Dale on a semi-regular basis. Finally, several Christian friends and I are involved in an unofficial homeless ministry that meets on a weekly basis, and we often speak with these two men.

Comments ()