Dinner on the Bissonnet Track, Part 1

The Bissonnet Track, a short drive down 59 from Sharpstown, has been the local buzz ever since HPD started blockading two streets after 10 PM to stop prostitution.

I wanted to investigate. So, like any sensible journalist, I decided to take my girlfriend out to dinner on the Bissonnet Track.

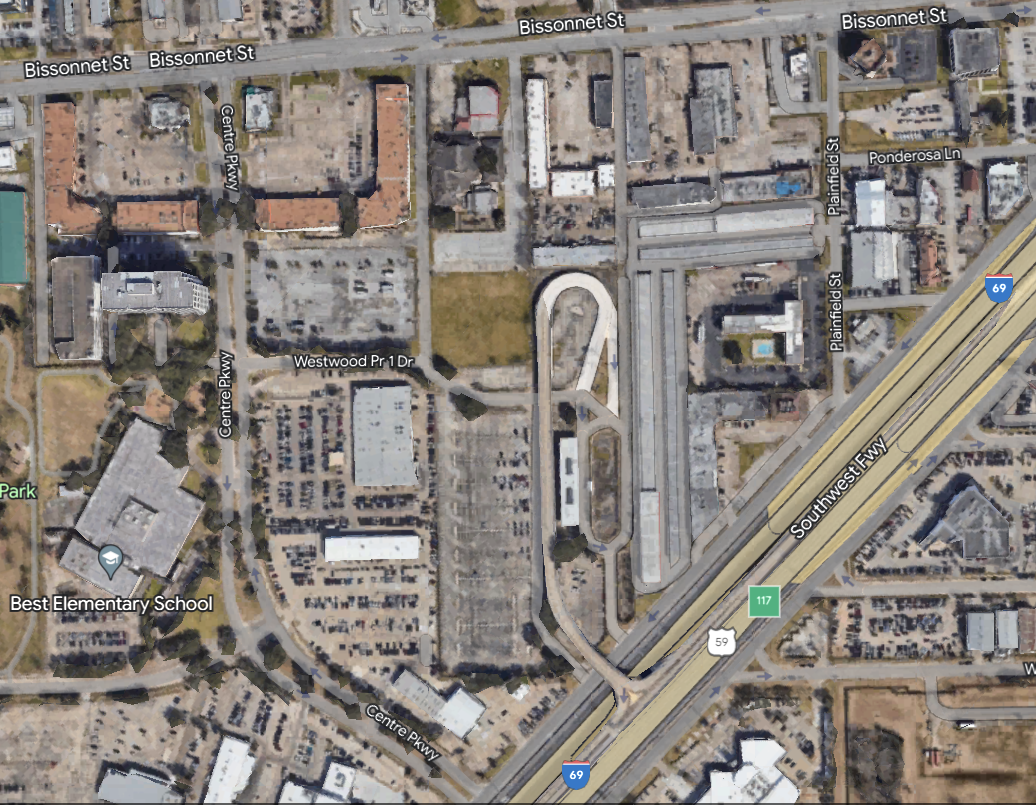

Don’t worry—I scouted the area first. I visited around lunchtime on Tuesday, June 6, and biked around, starting at the Burger King on Bissonnet and Plainfield St., then heading south down Plainfield past a three-story motel with red room doors and a yellow “Welcome” sign over the office.

Once I reached 59, I rode west along the frontage road, past an abandoned restaurant with windows barred and gutters sprouting weeds. I turned right onto Centre Parkway and headed north, past Best Elementary School, to meet Bissonnet again. Another right, and I was heading east down Bissonnet, past deep parking lots full of storefronts, back to Burger King.

According to Houston media outlets (and Redditors), I had just biked a major circuit on “the Track”—the route that johns used to circle, looking for prostitutes. The Houston Chronicle’s 2019 article series on “the Track” describes how pimps and prostitutes used to ply their trade here both night and day.

But I saw nothing.

It seemed the police efforts were working. Since May 16, HPD has been barricading Plainfield and Centre Parkway every night from approximately 10 PM to 5 AM—breaking two legs of the track—and patrolling the area during the daytime. If it wasn’t for the media stories, I never would have guessed that this used to be a hotspot for prostitution and trafficking.

The next morning, I returned to do more scouting. I had to know—was it really a good idea to bring my girlfriend here?

This time, I locked my bike outside the Burger King and went inside to order a Rodeo Burger. Thirty paper crowns lined the north windowsills. A family—what appeared to be a mother, two daughters, and a baby in a stroller—ate at a booth.

Supposedly (according to Reddit, at least), this used to be one of the hubs of the sex trade on Bissonnet. That’s probably why the sign on the door said no one could spend more than forty-five minutes in the restaurant, and why the bathroom wouldn’t open without a token from the front counter.

After washing the barbecue sauce off my hands, I strode to the counter and spoke to two employees. The younger woman translated one of my questions into Spanish for her coworker, whose name tag said “Xochitl.” Xochitl replied in Spanglish: there used to be “mucho people, mucho problem, mucho loco people” outside the Burger King. But now, “No mas. Fine.” In other words, after the police blockade began, there were no more crazy people.

While I was putting on my bike helmet outside, a young man in a black sweatshirt and camouflage bandana approached me. “Do you smoke?” he asked.

“Nope.”

He grinned goofily. “I was wondering if you smoked weed or something.” (I wondered what the “something” was.)

He walked back to a circle of men who stood in front of an unmarked white van and a U-Haul truck.

So I guess not all forms of unsavory activity had been stopped on Bissonnet. But he was rather polite.

The family exited Burger King and strolled to the bus stop just in front. I headed to Casa Honduras Restaurant at the far end of the adjacent parking lot. The owner, Angela, told me, “I’m okay with the police—it’s the ladies I don’t like.” She said the “ladies” still came out on the street at night, but that her business has been better since the blockade.

Still, her restaurant was surprisingly empty for lunchtime—only three vehicles sat outside. But it was a Wednesday.

To the west, the strip malls were ghost towns. I tried the doors of a restaurant, a market, a bookstore, and a barber shop. At 11:30 AM on a Wednesday, all were closed (even though one had posted hours saying otherwise). Another retail space had a “For Lease” sign in yellow letters, and another was empty except for construction workers bustling in and out.

Houston media outlets have frequently reported that the purpose of the blockade is to help the local community, including business owners. After all, many customers would prefer not to shop near prostitutes. But even without the prostitutes, it seemed like local businesses were still struggling.

In front of his shop, a local mechanic told me his business had been “dead” since the shutdown. He blamed the media for spotlighting the prostitution on the Bissonnet Track in recent months: “after they put the area on TV,” his business “went down, then up, then down again.” He said that many of his customers have left.

For a moment, I felt bad about being a journalist, which was why I didn’t press him for his name as he walked away. But I realized that my story might put the area in a less negative light.

Of course, I didn’t know yet. Bissonnet was quiet during the day, but what about at night? Well, at 7:45 PM on Wednesday, June 7, my girlfriend and I were about to find out.

What’s life without a little adventure?

To be continued. Read Part 2 here.

Left to Right: Centre Parkway facing Bissonnet, Centre Parkway facing the 59 Frontage Road, Plainfield St. facing Bissonnet.

Comments ()