Dinner on the Bissonnet Track, Part 2

Yes, I’m that journalist who thought it was a great idea to investigate the Bissonnet Track blockade by bringing my girlfriend there for dinner.

I had scouted the area that morning, and I hoped the Track would be as quiet at night as it had been during the day. At 7:45 PM on June 7, my girlfriend and I pulled up to Finger Licking Restaurant, an African eatery on Bissonnet and Centre Parkway—another corner of the Track. Finger Licking had just moved into the old Pappa’s BBQ location (after already moving to a strip mall from their deteriorating location on the other side of Center Parkway). Now three Finger Licking’s stood within about five hundred feet of each other.

We exchanged the fading sunlight for the soft, warm light of the interior. Almost everything was made of wood—the floor, ceiling, wall panels, and the waist-high wall that split the room in half. Four men sat around a table on cushioned white chairs, bantering with another man who strode toward them from the counter. A woman sat alone, wearing white earbuds.

Not the busiest place, but it was getting late—and it was a Wednesday.

Ajoke, the waitress, took our order from behind the counter. We sat.

A pale wooden mask, topped by a brown and red carved bird, stared down from the brick column in the center of the room. A few more customers came in for takeout.

The jollof rice and goat were delicious, but they made me sweat. (I’d say which country’s style of jollof it was, but I don’t want to spark another skirmish in the Great Jollof War.)

Other than the fact that my girlfriend and I were both periodically scribbling in notebooks, it was a pretty normal date.

Ajoke told us that before the blockade, customers complained and didn’t want to bring their kids to the restaurant because of the “ladies” on Centre Parkway.

The prostitutes had also frequently entered the restaurant and had altercations with employees. One had even pepper-sprayed the manager, said Ajoke.

Now, except for the noise of three TVs, the restaurant was calm. Ever since the blockade, said Ajoke, more customers were coming, although she couldn’t provide an exact number.

The Burger King on the other end of the Track was quiet too. Between around 9:15 and 10:00 PM, five male customers entered and exited while we had dessert. Just after 10 PM, a carload of women showed up, tried the locked door while we stood outside, and left. Other than that, nothing.

We waited in the parking lot for police to show up. At 10:21 PM, two police cars whizzed past and turned right onto Plainfield, just behind the Burger King. By the time we exited the car and strolled over to interview them, they were gone. It was as if the orange reflective barricades and safety cones had appeared by magic. (The police returned to staff the barricade later.)

We walked down to the other end of Plainfield Street, which the police had barricaded off from the 59 frontage road. Even the OYO Hotel appeared dead from the outside, other than one woman who sat on the curb outside the office, and one white truck that darted into the parking lot and left within three minutes.

Around 11 PM, we hopped back in the car and drove back to Finger Licking. Nothing was unusual except the barricades set up outside.

But two or three blocks west, we saw them.

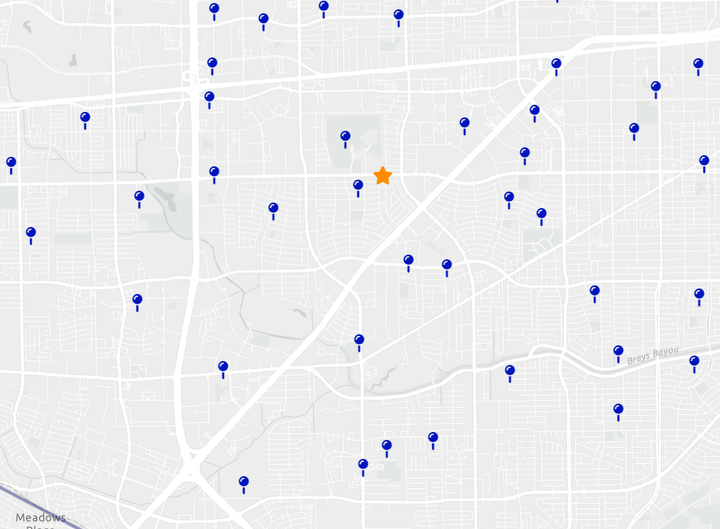

I won’t say the exact locations because I don’t want to give the hookers free advertising. But eight or nine women (not wearing many clothes) dotted various sidewalks and street corners.

On one hand, this was nothing compared to the tales of the Track in its “heyday.” The prostitutes were few and scattered.

On the other hand, it made me wonder—yes, we saw zero prostitution on the main circuit of the Bissonnet Track, but is the problem just moving elsewhere? If so, what neighborhoods will be affected?

Women are especially likely to be relocated if they are already being trafficked—forced into prostitution against their will. According to David Gamboa, communications director for anti-trafficking organization Elijah Rising, “It's likely they are still being trafficked either online and in hotels, in strip clubs, or in another city. Many of the women on Bissonnet don't stay local. Their pimp moves them around to other cities.”

The new police blockade may be one step toward restoring the struggling business district along Bissonnet—and protecting the local children who attend Best Elementary School—but what about the trafficked women? We may be able to say, “Not in my backyard,” but it will happen in someone’s backyard, to someone’s daughter, sister, or mother. Helping them will take a lot more than shutting down streets.

District J Council Member Edward Pollard intends to do more than shutting down streets. Read about his long-term ideas for the Bissonnet Track here.

Comments ()