How Sharpstown’s Neff Elementary Grew 14 Points on Accountability in 2023-24: Former Principal Amanda Wingard Celebrates and Bids Farewell

Neff Elementary improved 14 points on its accountability score during Amanda Wingard’s last year as principal. Paradoxically, she credits the fact that she and her teachers voluntarily implemented some of the reforms advocated by Mike Miles—the superintendent who forced her to resign this May without explaining what standards he used to make that decision. Now, as Wingard bids farewell to the school she attended as a child and worked at for 21 years, she finally feels peace. In the past, when asked if she would consider leaving, she said, “Yes, if I felt that I was leaving Neff in a better place.” Now, she believes she is.

For the second year in a row, school districts filed a lawsuit to block the Texas Education Agency from releasing public schools’ A-F accountability scores. Like last year, HISD again used the TEA’s data and methodology to calculate its own ratings anyway. It gave Neff a 67 (high D) for the 2022-23 school year and an 81 (low B) for 2023-24—a 14-point leap.

During Wingard’s last year at Neff’s helm, the percentage of her students meeting grade level on the STAAR rose from 31% to 34%, according to Good Reason Houston's database. Neff’s 4th- and 5th-grade scores improved most: for each, the numbers of students approaching and meeting grade level in reading rose by 3% or more. Fifth-grade math even jumped from 29% to 48% of students meeting grade level—a 19% leap.

Overall, this year’s third graders performed slightly worse than last year’s. But they also came to Neff with lower English language proficiency, based on their 1st- and 2nd-grade TELPAS scores.

Wingard said that much of Neff’s accountability leap came from smaller improvements that may not show on a typical STAAR breakdown. For example, Neff did well on Academic Growth, which measures how individual 4th and 5th-graders scored compared to their past selves.

How did Neff grow in a year when many school districts across Texas are claiming that the new STAAR test and accountability standards unfairly lowered their ratings?

I sat down with Wingard at Spanky’s Pizza on Bellaire to reflect on the last year—and twenty-one years at her “special” school in Sharpstown.

How Are Schools Rated? Click This Dropdown for More

70% of a school’s rating comes from one of three "component scores": Student Achievement, Academic Growth, or Relative Performance—whichever is highest. For Neff, that was Academic Growth, based on how individual 4th and 5th graders performed this year compared to their personal STAAR scores last year. The rubric awards one point for every student who grew at least half a level (e.g. from Low Approaches Grade Level to High Approaches Grade Level). Then the total number of points gets converted into a scaled score.

30% of the rating comes from a fourth component score: Closing the Gaps, which measures how closely various groups within the school—including Emergent Bilinguals, Economically Disadvantaged, and the previous year’s two lowest-performing ethnic groups—are approaching their STAAR performance targets set by the state.

According to HISD, Neff’s Academic Growth score was 80, and Closing the Gaps was 83.

Going All-in on Phonics

For decades, public education has been a battleground between two methods of teaching kids how to read: phonics and “cueing.” Phonics teaches children to sound out words letter by letter. Cueing teaches children to identify words based on three “cues”: the context, the first letter of the word, and the accompanying picture.

Like thousands of other American educators, Wingard was trained to believe that the cueing method is superior. But when I interviewed her last June, she had just finished listening to the podcast Sold a Story by American Public Media journalist Emily Hanford. Hanford makes the case that cueing harms students and phonics is the key to teaching children how to read. She convinced Wingard.

In the past, Neff taught a mix of phonics and cueing, but in June 2023, Wingard was ready to move fully to phonics. Like other schools across HISD, Neff used the phonics-based reading curriculum Amplify in 2023-24. “No cueing,” said Wingard.

She praised Amplify, especially the phonics element. “I like it. But it’s very high level, very rigorous, so we did have to adjust some…based on what our students needed. But it really worked.” In Amplify, students hone their skills by reading about “high-level topics like ancient Greece and the human body, so that stuff was really interesting and they really got into it.”

Volunteering to Implement “NES-lite”

This school year, Neff joined Miles’ New Education System. Last year, Neff was not an NES school, but Wingard and her teachers voluntarily implemented what she said could be called “NES-lite.”

Protesters have harshly criticized the NES—especially the Team Centers, which many of Miles' opponents have misleadingly called “discipline centers.” But I visited Team Centers at Sharpstown’s Sugar Grove Academy, and they were primarily a place for advanced students to do advanced work. Team Centers are just one part of “differentiated instruction,” a practice based on the idea that different students learn in different ways and at different rates. Midway through an NES class period, teachers will give students a short quiz called a Demonstration of Learning (DOL). Students who show that they understood the day’s lesson get sent to the Team Center for advanced study (usually individual worksheets). Students who did not grasp the lesson stay in the classroom for a re-teach.

Wingard and her teachers started using differentiated instruction at Neff last school year. Without the larger budget of an NES school, they managed to administer daily DOLs and run a “learning center”—essentially a Team Center with more options than just worksheets. They also focused on helping struggling students: “We did a lot with being intentional for reteaching our kids who needed intervention.”

Adapting NES “Differentiated Instruction”

Wingard doesn’t agree with every piece of the NES. She thinks it should be more flexible, especially for Emergent Bilingual (EB) students—usually recent immigrants who are still learning basic English. If a 4th or 5th-grader consistently fails their DOLs due to a language barrier, then it may not help them to sit through a reteach in English, said Wingard. Instead, they may need to join “a small group where we go back to doing some first- and second-grade phonics” to hone their basic English skills.

She also suggested that it’s not always exciting—or incentivizing—to tell students, “You did well, so go work on a packet in the Team Center.” She thinks Team Centers should offer more options, like guided research projects, novel studies, literature circles, and “actually working in a team.” Last year, Neff’s learning center often allowed students to do group work on topics they were interested in. “The kids were excited to do well so they could go and have…more of a choice.”

Principals Coaching in Classrooms

Wingard and her assistant principals also co-opted another part of the New Education System: spending more time in classrooms coaching teachers.

Like all school leaders under Miles, they also had to conduct spot observations: a principal or AP watches a teacher for part of a class period and rates their performance. Observations make up about 30% of a teacher’s effectiveness score, which is used to determine employment and pay. Wingard thinks that the spot observations contribute to a “culture of fear” at HISD: “Everyone’s scared they’re going to lose their job if they make a mistake.”

She said she’s been talking to other principals, and many lost one to ten teachers due to poor spot observation performance. Some principals graded harder on spot observations because they wanted teachers to grow, and then were surprised when so many teachers lost their jobs, she added.

But at Neff, zero teachers were asked to resign, said Wingard. She attributes that to taking a gracious approach to spot observations: “We really worked with our teachers who were struggling—giving feedback, doing multiple observations.”

“We need to make sure…we’re giving coaching opportunities,” she said. In theory, that’s supposed to happen at every NES school. Miles has touted coaching for teachers as a benefit of the NES from the beginning. But how much coaching really happens? And how high-quality is it? That depends on the principal.

For some busy school leaders, the eight spot observations required per teacher per year may become just more paperwork on their checklist. Some teachers at Sharpstown High claimed that under Principal T.J. Cotter, last year’s spot observations were short and unhelpful. Said first-year teacher Kristina Samuel, “We get told how we do it wrong all the time, but never told how to do it right.”

Wingard thinks it’s important to give constructive feedback: not just, “Hey, you need to get better on this,” but, “Hey, here are some ways on how to do it.”

Moving on from the “Culture of Fear”

Wingard said that “two different people that were my direct bosses” tried to deter her from speaking out publicly, telling her that it could hurt her future career prospects. Instead, after she posted about her forced resignation on Facebook, “I had multiple calls and multiple inquiries and offers”—including some of her former superintendents and bosses asking her to move to their districts, she said.

In July, she announced that she had accepted a school leader job at KIPP Climb in southeast Houston. She wished that her time at Neff had ended “in a more positive way,” but then she calculated Neff’s accountability rating and saw the 14-point jump. She was elated. “Oh my goodness—this is God’s way of telling me, ‘Job well done.’ I’ll remember that as the exclamation point of my career.”

She also finds comfort in the words of a friend who told her, “This was what you needed to move on.” If HISD hadn’t forced her to resign, she may not have moved on to a “new challenge.” Transferring to KIPP has “pushed me out of my comfort zone,” but Wingard is embracing it.

New Mission at KIPP

At KIPP Climb, Wingard will be implementing some of the same strategies she used at Neff last school year. Her new school will use Amplify Reading “all the way through” for the first time, and has used Eureka Math—the same curriculum Wingard used in HISD—for years. KIPP also practices “reteaching and intervention,” she said.

Wingard appreciates KIPP’s culture. Compared to HISD, “The feeling of support [at KIPP] is just so different, and just the feeling of joy and making sure kids learn academically but also have a joyful experience at school.” She remembers sitting in a meeting and realizing, “I get to plan a field trip”—two or three, actually. She also said that KIPP has been receptive to her ideas, like planning one academic field trip and one fine arts trip.

Wingard is glad she still gets to work with many bilingual students. Neff’s student body was 75% Emergent Bilingual in 2022-23, and KIPP Climb’s was 27% EB. She calls EBs “my heroes” because they face the challenges of coming to a new country and learning a new language on top of the typical challenges students face.

KIPP Climb’s 2023-24 STAAR scores were low—only 26% met grade level, according to Good Reason—and Wingard anticipates the school’s accountability rating will be a D. “But they have had a lot of success with their early childhood, with the phonics…so we’re going to keep building on that,” she said.

Wingard has flipped a D school to a B school before. She welcomes the challenge.

Farewell to Neff and Sharpstown

Overall, Wingard feels she has left Neff in a better place. Her only worry is Neff’s high teacher turnover last year. Going into 2023-24, Neff had a staff of veteran teachers who Wingard credited with much of the school’s success. She had only hired one new teacher. But she said that four teachers retired at the end of the school year, and another ten or more left after the district forced her to resign.

Still, Wingard has high hopes for Neff. She says she is “super in support” of new principal Mahalet Negussie: “Having fresh eyes and a fresh vision could be a really good thing for [Neff].”

She wants Neff students and parents to know she’ll miss them: “Thank you for being such a great part of my experience as principal. I’m so proud of the work that they did this past year—and these past few years managing and handling a pandemic.”

She’ll also miss Sharpstown: “I am so thankful to that community…. It will always be home to me.”

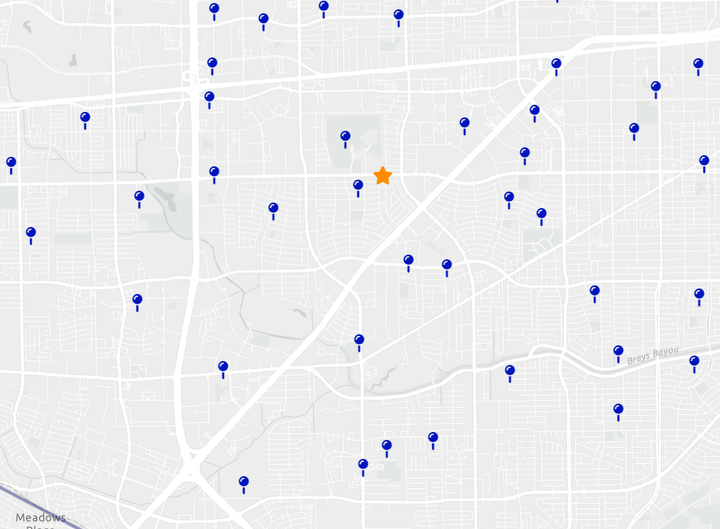

See how other schools in Sharpstown did on the latest accountability ratings. Hint: Neff outperformed the others.

Comments ()