Climbing off the Streets: Leroy Conner's New Life after Homelessness

“This is my store.” Pride rings in Leroy Conner’s voice as he strolls between the shelves of chips, soda, backpacks, shoes, and more.

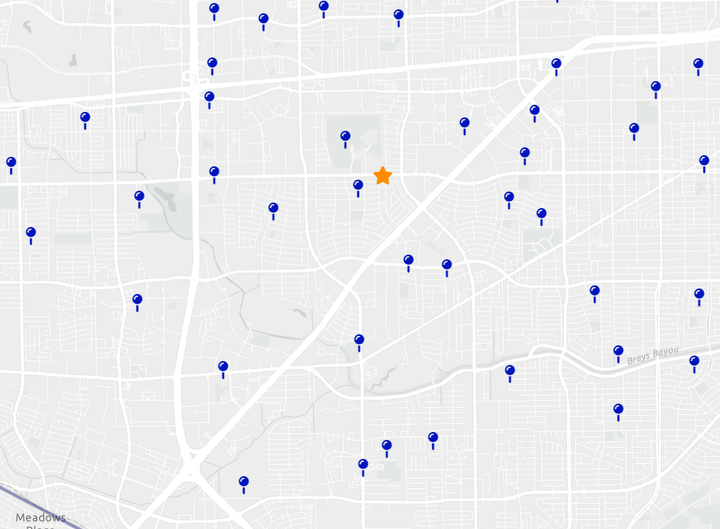

Last December, he was living under the Southwest Freeway in Sharpstown, recycling for a living. Nine months later, he wears a dark blue uniform with a “Security Officer” patch on his chest.

Few chronically homeless people achieve what Conner has. After nearly eighteen years on the streets of Houston, and with zero help from government housing vouchers, he’s keeping a roof over his head by working a job.

Officially, he doesn’t own the Gulfton convenience store, but he takes ownership of his work. He manages deliveries, stocks shelves, greets customers, helps them find items, fixes the ice machine, and serves as guard.

But a year ago, says Conner, “There were days I’d wake up in the morning with no money, hungry.” He wouldn’t fly a sign. Instead, he’d hop on his bike to hunt for things to sell: copper wire salvaged from construction dumpsters, abandoned merchandise, and more. “I’d rather earn my money, and then I did it myself—I don’t want anybody to do it for me.”

But he also had “a bad substance problem” and had mostly given up on hope for the future. “I was fatalistic…I only cared for the moment.”

A turning point came last fall when a local pastor and his daughter visited him and prayed with him. “What is a pastor doing coming up under the bridge to homeless people with his daughter?” he wondered. “I was so impressed, and I thought, 'Maybe I do have a chance.'”

When the pastor asked if he had prayer requests, Conner responded, “Ask God to make my life a little easier.” He sees where he is today as an answer to that prayer.

In January, he got his photo ID back—a vital ticket to participation in society. Then he got news from a friend who often bought merchandise from him. The friend was buying a convenience store, and he wanted Conner to be the security guard.

The store’s previous owners had been on the brink of going out of business, said Conner. “It had a bad reputation. The toilet was never clean. There was no toilet paper… They lost their patronage.”

After Conner started working there in January, he and the new owner began the task of turning the store around.

Strolling through the aisles, Conner gestures to the many shelves and racks that he arranged. He points to a wall of shirts, hats, and jackets. “This is the clothing department.” He built one of the racks using a long, wooden pole he found at the 99-Cent store when it was closing.

He shows off an area in the back corner. “This is my workshop.” Pointing to the light green key machine, he says he’s learned how to operate it and even made some of the store keys hanging on a long silver chain from his belt.

While telling his story, he swivels his head toward the door every time the doorbell tinkles. He says that he works hard to show courtesy and humility so that customers “walk out more peacefully than they did when they first walked in.”

To him, the store has become a “haven.” He feels less worried, more “grounded” and “happy” than a year ago.

But sometimes, Conner still feels the streets calling. More than once in the past nine months, he temporarily returned to his old perch: wooden pallets nestled under the bridge where he used to live with his old friend Dale Malone.

It might seem strange to someone who has never been homeless, but Conner isn’t alone. I know a homeless man named Tim who was given an apartment by the government but still returned to sleep under his old bridge several nights a month. Eventually, he abandoned his apartment altogether.

Why go back? Conner was blunt. “The pull of the streets is not having any obligations. No responsibilities. You figure…no obligations, no responsibilities, equals no worries.”

But he added a qualifier: “If you’re a shallow person.” Now, he realizes, “If you don’t have any obligations and you don’t have responsibilities, you don’t have no life. Life comes with that.”

He can’t shake the memory of a man he worked for years ago, cleaning a parking lot. The man, who owned properties around Bellaire and Rice, told Conner, “I do all this for my grandchildren.”

He struck Conner as a “real man,” prompting a moment of self-reflection: “I’ve always been in tune with instant self-gratification. For a real man, self-gratification is the last worry. He has things he wants to achieve that has nothing to do with self-gratification. So he strives for someone else and not himself…. That’s one heck of a man.”

Who is Conner striving for?

He spends time praying and meditating. “I’m serving a higher power whose purpose is more important than mine.”

He’s also found a “new family”: the store owner and his family. He says he feels “more love” from them than he did from his siblings while growing up.

And his long-term goals include getting his driver’s license and a car. His new philosophy? “Make preparations today for tomorrow.”

But it’s still been a battle.

Around three weeks ago, Conner biked back to the bridge. “I was about ready to go up that incline, and then I stopped my bike, I looked up there…and I kid you not, I think a tear come down.” He shook his head, walked his bike across the street, and sat down, thinking, “Why do I keep going back?”

He decided that he'd had enough.

“Lord, let this be the last.”

Miss the previous articles in this series? Find them below.

Comments ()