Climbing off the Streets, Part 6: The Waiting Game

On the afternoon of Sunday, February 11, Dale Malone and I pull up to the Gulfton convenience store where Leroy Conner now works as a security guard. The friends haven’t seen each other since a chance meeting at the Social Security office a week and a half earlier. But they have a common goal: home.

Dressed sharply in a black denim vest, Leroy beams, proud of his progress and happy to see Dale. Dale is glad too: in his words, Leroy is his “hero.” But Dale’s undercurrent of sadness surfaces as we drive to a Sharpstown Denny’s. Discouragement is written in his frown.

Over biscuits and gravy, the homeless men compare notes. Ever since both got their IDs at the Rosenberg DPS on January 2, they’ve been making progress in their quest to get off the streets for good. Leroy has made it further than Dale, but both are stuck in the waiting game.

Homeless people often find themselves in a tangle of Catch-22s: it’s hard to get housing without a stable job, but it’s hard to get a stable job without housing, and it’s nearly impossible to get either without a valid photo ID. Climbing out of that mess requires working with the government—and that takes time, with plenty of chances for setbacks along the way.

Dale and Leroy used to sleep under the same bridge, but they parted ways after a friend offered Leroy a security job three miles away. But Dale and Leroy still want to become roommates. Splitting rent will help them afford an apartment.

Right now, Leroy’s security job doesn’t pay enough for him to afford even half of an apartment, but he’s reluctant to leave because the job comes with temporary housing (for him, at least).

Even at 64, Leroy is able-bodied and willing to work, but he hopes that his retirement benefits will help him afford to rent a place with Dale. But the government still needs to decide whether to grant him his benefits. A week and a half earlier, the Social Security office told him he would have to wait 30 days for an answer.

At 59, Dale can’t claim retirement, but he lacks a college education and struggles with memory lapses, so a traditional office job is probably out of the question.

He worked construction most of his life, even running his own roofing and remodeling company, but he says that now, it’s hard to get a construction job in Houston without knowing Spanish. He also says his six strokes and COPD make it difficult for him to perform strenuous manual labor (and his doctors advise against it).

Still, he says he’s open to work if anyone will hire him, and he sometimes does odd jobs like picking up trash or cleaning restrooms for the small businesses near his bridge. He also dreams of getting a box truck and a vending bike to start a barbecue business that would employ other homeless people.

He also says his multiple strokes make him eligible for a government disability check. It’s not enough for him to afford an apartment on his own, which is why he needs a roommate.

The problem is, he needs a safe place to save up money while he looks for an apartment (homeless people are often victims of theft). But local banks won’t let him open an account without the hard copy of his photo ID.

Dale and Leroy both received temporary paper copies of their IDs at the DPS on January 2, but they had to wait for the hard copies to come in the mail.

Leroy’s Texas ID arrived weeks ago, but Dale still hasn’t received the hard copy of his driver’s license.

When we visited the Harris County Courthouse Annex in Gulfton, he was able to get a copy of his birth certificate in about fifteen minutes using his temporary paper ID. At the Social Security office, he was able to apply for a new copy of his Social Security card after waiting for an hour and a half. He hadn’t been able to do any of this before he got his temporary ID.

But he still can’t open a bank account.

Later, on February 15, Dale called the Texas DPS while sitting on a curb eating a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich. After forty-five minutes of hold music, a woman picked up. She said that the DPS had mailed out his license on January 9, but for some reason, the post office returned it on January 26. Dale asked her to re-mail the license, and she said it would take another 10-14 business days.

“I’m gonna wait out there every morning for the mailman to come,” he told her.

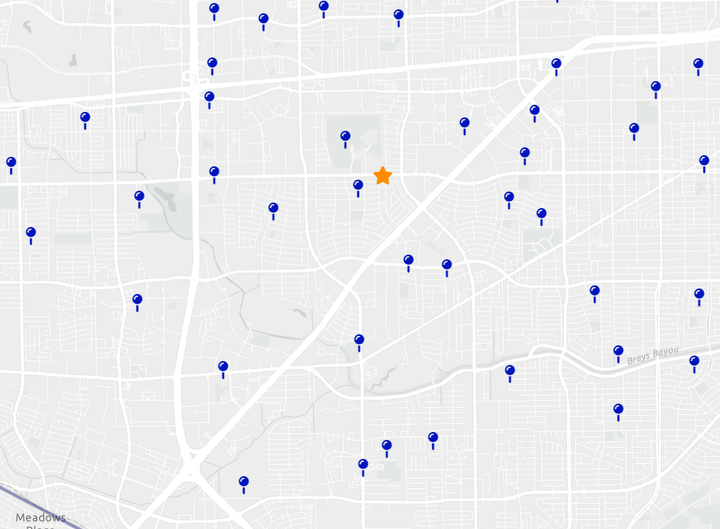

If all goes well, Dale may get the hard copy of his license around the same time Leroy gets his retirement benefits. Then they’ll need to find a local, affordable apartment complex that accepts tenants with low credit and a long rental history gap.

Back at Denny’s, Leroy shows us his old homeless ID issued by Harris County. A variety of organizations in Houston didn’t accept it, he says, although the Rosenberg DPS eventually used it as proof of identity when he applied for his state-issued Texas ID.

He points to a word on the white plastic card: “Homeless.” He thinks that’s why people looked down on him when they saw his old ID.

Then he shows us his new Texas ID, which has worked where his homeless ID didn’t. Why?

He points. “It doesn’t have the word ‘homeless’ on it.”

Subscribe for free so you don't miss the next article in this series, where I follow Dale and Leroy in their quest to climb off the streets of Sharpstown.

Miss the first article in this series? Read it here.

Conflict of Interest Statement: It should be obvious, but I take a personal interest in this story. After all, I drove Dale and Leroy to Rosenberg. I've known them for a while, especially Dale (I've spent countless hours in conversations with him over the last four years). That's why I used their first names instead of following the standard journalistic practice of using last names. I'm taking a more personal approach for this series. Both men have also attended my church—Dale on a semi-regular basis. Finally, several Christian friends and I are involved in an unofficial homeless ministry that meets on a weekly basis, and we often speak with these two men.

Comments ()